Gary Klein's Triple Path Model of Insight

The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights

In 1936 Graham Wallas, co-founder of the London School of Economics, published The Art of Thought, outlining the four stages of the creative process. This pre-dates, by at least a decade, James Webb’s A Technique for Producing Ideas.

Wallas’s model “is still the most common explanation of how insight works. If you do any exploration into the field of insight, you can’t go far without bumping into Wallas, who is the epitome of a British freethinking intellectual," writes Gary Klein in Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights.

The Creativity Question, published in 1976, preserves Wallas’s “Stages of Control" and presents his model of insight: (1) preparation; (2) incubation; (3) illumination; and (4) verification.

In Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights, Klein summarizes:

During the preparation stage we investigate a problem, applying ourselves to an analysis that is hard, conscious, systematic, but fruitless.

Then we shift to the incubation stage, in which we stop consciously thinking about the problem and let our unconscious mind take over. Wallas quoted the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, who in 1891 at the end of his career offered some reflections on how this incubation stage feels. After working hard on a project, Helmholtz explained that “happy ideas come unexpectedly without effort, like an inspiration. So far as I am concerned, they have never come to me when my mind was fatigued, or when I was at my working table. They came particularly readily during the slow ascent of wooded hills on a sunny day."

Wallas advised his readers to take this incubation stage seriously. We should seek out mental relaxation and stop thinking about the problem. We should avoid anything that might interfere with the free working of the unconscious mind, such as reading serious materials.

…

Next comes the illumination stage, when insight bursts forth with conciseness, suddenness, and immediate certainty. Wallas believed that the insight, the “happy idea," was the culmination of a train of unconscious associations. These associations had to mature outside of conscious scrutiny until they were ready to surface. Wallas claimed that people could sometimes sense that an insight was brewing in their minds. The insight starts to make its appearance in fringe consciousness, giving people an intimation that the flash of illumination is nearby. At this point the insight might drift away and not evolve into consciousness. Or it might get interrupted by an intrusion that causes it to miscarry. That’s why if people feel this intimation arising while reading, they often stop and gaze out into space, waiting for the insight to appear. Wallas warned of the danger of trying to put the insight into words too quickly, before it was fully formed.

Finally, during the verification stage we test whether the idea is valid. If the insight is about a topic such as mathematics, we may need to consciously work out the details during this final stage.

Wallas noted that none of these stages exist in isolation.

In the daily stream of thought these four different stages constantly overlap each other as we explore different problems. An economist reading a Blue Book, a physiologist watching an experiment, or a business man going through his morning’s letters, may at the same time be “incubating" on a problem which he proposed to himself a few days ago, be accumulating knowledge in “preparation" for a second problem, and be “verifying" his conclusions on a third problem. Even in exploring the same problem, the mind may be unconsciously incubating on one aspect of it, while it is consciously employed in preparing for or verifying another aspect. And it must always be remembered that much very important thinking, done for instance by a poet exploring his own memories, or by a man trying to see clearly his emotional relation to his country or his party, resembles musical composition in that the stages leading to success are not very easily fitted into a “problem and solution" scheme. Yet, even when success in thought means the creation of something felt to be beautiful and true rather than the solution of a prescribed problem, the four stages of Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, and the Verification of the final result can generally be distinguished from each other. (The Creativity Question)

If you talk to anyone about insight today, most people are familiar with the model Wallas proposed.

“It’s a very satisfying explanation that has a ring of plausibility," writes Klein, “until we examine it more closely."

Klein points to many counterexamples where people had insights that came unexpectedly, without a preparation stage. A lot of people aren’t wrestling with a problem when they come up with an accidental insight.

According to Wallas, when we’re stuck and need to find an insight that will get us past an impasse, we should start with deliberate preparation. … One flaw in Wallas’s method is that his sample of cases was skewed. He only studied success stories. He didn’t consider all the cases in which people prepared very hard but got nowhere.(Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights)

Specific preparation doesn’t always lead to insights. And the people who gain insights may or may not follow Wallas model, so perhaps it is incomplete.

We need another theory.

Discontinuous Discoveries

Sometimes shifts in thinking are not about making minor adjustments or adding details. Sometimes we fundamentally shift core beliefs. This allows us to see the problem in a new way and may lead to insight. We shift from a poor story to a better one. These are discontinuous discoveries.

Insights shift us toward a new story, a new set of beliefs that are more accurate, more comprehensive, and more useful. Our insights transform us in several ways. They change how we understand, act, see, feel, and desire. They change how we understand. They transform our thinking; our new story gives us a different viewpoint. They change how we act. … Insights transform how we see; we look for different things in keeping with our new story. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

In Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel makes an important observation, “Insight cannot be taken back. You cannot return to the moment you were in before." After insight, everything is different.

Insights are unique is some other ways:

When they do appear, they are coherent and unambiguous. They don’t come as part of a set of possible answers. When we have the insight, we think, “Oh yes, that’s it." We feel a sense of closure. This sense of closure produces a feeling of confidence in the insight. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

The Difference Between Insight and Intuition

Intuition is the use of patterns they’ve already learned, whereas insight is the discovery of new patterns. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

The Role of Stories

Stories are a way we frame and organize the details of a situation. There are other types of frames besides stories, such as maps and even organizational wiring diagrams that show where people stand in a hierarchy. … These kinds of stories organize all kinds of details about a situation and depend on a few core beliefs we can call “anchors," because they are fairly stable and anchor the way we interpret the other details. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

And anchors can change. They change when we get new information. They change when we shift our beliefs.

What causes us to change our story? Klein proposes five strategies connections, coincidences, curiosities, contradictions, and creative desperation.

In all of these cases we change our story.

When faced with creative desperation, we try to find a weak belief that is trapping us. We want to jettison this belief so that we can escape from fixation and from impasse. In contrast, when using a contradiction strategy, we center on the weak belief. We take it seriously instead of explaining it away or trying to jettison it. We use it to rebuild our story. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

When we’re desperate, we’re more likely to attack a weak anchor and give something a try.

In times of desperation, we actively search for an assumption we can reverse. We don’t seek to imagine the implications if the assumption was valid. Rather, we try to improve the situation by eliminating the assumption. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

But changing our story is not the only way to gain insight. We can also add new anchors.

The Triple Path

In the end, Klein came up with the tripe path model of insight, which tries to capture the similarities between the strategies.

The connection path is different from the desperation path or the contradiction path. We’re not attacking or building on weak anchors. When we make connections or notice coincidences or curiosities, we add a new anchor to our beliefs and then work out the implications. Usually the new anchor comes from a new piece of information we receive.

…

I’ve combined the connections, coincidences, and curiosities in the Triple Path Model. They have the same dynamic: to build on a new potential anchor. They have the same trigger: our thinking is stimulated when we notice the new anchor. Coincidences and curiosities aren’t insights in themselves; they start us on the path to identifying a new anchor that we connect to the other beliefs we hold. Connections, coincidences, and curiosities have the same activity: to combine the new anchor with others. This path to insight doesn’t force us to abandon other anchors. It lets us build a new story that shifts our understanding. This path has a different motivation, a different trigger, and a different activity from the contradiction and the creative desperation paths. Nevertheless, like the other two paths, the outcome is the same: an unexpected shift in the story.

Each of the three paths, the contradiction path, the connection path, and the creative desperation path, gets sparked in a different way. And each operates in a different fashion: to embrace an anomaly that seems like a weak anchor in a frame, to overturn that weak anchor, or to add a new anchor. Future work on insight is likely to uncover other paths to insight besides the three shown in the diagram. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

Other people weren’t wrong, they were just following one path.

The Triple Path Model shows why earlier accounts aren’t wrong as much as they are incomplete. They restrict themselves to a single path. Researchers and theorists such as Wallas who describe insight as escaping from fixation and impasses are referring to the creative desperation path. Researchers who emphasize seeing associations and combinations of ideas are referring to the connection path. Researchers who describe insight as reformulating the problem or restructuring how people think have gravitated to the contradiction path. None of them are wrong. The Triple Path Model of insight illustrates why people seem to be talking past each other. It’s because they’re on different paths. (Seeing What Others Don’t)

If you’re interested in learning more about the creative process, you really need to read Seeing What Others Don’t (compliment with A Technique For Producing Ideas and Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights.)

Filed Under: Books, Creativity, Culture, Gary Klein, Graham Wallas, Innovation, Philosophy, Psychology, Science

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Einstein: Combinatory Play is the Essential Feature of Thought

Einstein on The Essential Feature of Productive Thought

There is a view, to which I subscribe, that a lot of innovation and creativity comes from the combination of worldly wisdom, perspective, accumulating existing ideas, failures from multiple disciplines, amongst other things. These ideas — sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously tossed around in our head — combine into something new. This is part of the reason that creativity and innovation is hard. You can’t just pick up a single book or thread of knowledge and have it deliver results.

This beautiful Steve Jobs quote sums it up nicely.

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while."

***

In 1945 Jacques S. Hadamard surveyed mathematicians to determine their mental processes at work by posing a series of questions to them and later published his results in An Essay on the Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field.

It would be very helpful for the purpose of psychological investigation to know what internal or mental images, what kind of “internal words" mathematicians make use of; whether they are motor, auditory, visual, or mixed, depending on the subject which they are studying.

Especially in research thought, do the mental pictures or internal words present themselves in the full consciousness or in the fringe-consciousness …?

Einstein‘s response to the French mathematician, found in his Ideas and Opinions, shows the physicist’s mind at work and the value of “combinatory play."

My Dear Colleague:

In the following, I am trying to answer in brief your questions as well as I am able. I am not satisfied myself with those answers and I am willing to answer more questions if you believe this could be of any advantage for the very interesting and difficult work you have undertaken.

(A) The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be “voluntarily" reproduced and combined.

There is, of course, a certain connection between those elements and relevant logical concepts. It is also clear that the desire to arrive finally at logically connected concepts is the emotional basis of this rather vague play with the above-mentioned elements. But taken from a psychological viewpoint, this combinatory play seems to be the essential feature in productive thought — before there is any connection with logical construction in words or other kinds of signs which can be communicated to others.

(B) The above-mentioned elements are, in my case, of visual and some of muscular type. Conventional words or other signs have to be sought for laboriously only in a secondary stage, when the mentioned associative play is sufficiently established and can be reproduced at will.

(C) According to what has been said, the play with the mentioned elements is aimed to be analogous to certain logical connections one is searching for.

(D) Visual and motor. In a stage when words intervene at all, they are, in my case, purely auditive, but they interfere only in a secondary stage, as already mentioned.

(E) It seems to me that what you call full consciousness is a limit case which can never be fully accomplished. This seems to me connected with the fact called the narrowness of consciousness (Enge des Bewusstseins).

Remark: Professor Max Wertheimer has tried to investigate the distinction between mere associating or combining of reproducible elements and between understanding (organisches Begreifen); I cannot judge how far his psychological analysis catches the essential point.

***

Still curious? Combinatory play is one of the principles of Farnam Street. It’s so important I’ve incorporated it into the Re:Think Workshops.

Filed Under: Albert Einstein, Books, Creativity, Innovation, Letters, Philosophy

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Eight Things I Learned from Peter Thiel’s Zero To One

Eight Things I Learned from Peter Thiel’s Zero To One

Peter Thiel is an entrepreneur and investor. He co-founded PayPal and Palantir. He also made the first outside investment in Facebook and was an early investor in companies like SpaceX and LinkedIn. And now he’s written a book, Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, with the goal of helping us “see beyond the tracks laid down" to the “broader future that there is to create."

Zero To One is an exercise in thinking. It’s about questioning and rethinking received wisdom in order to create the future.

Here are eight lessons I took away from the book.

1. Like Heraclitus, who said that you can only step into the same river once, Thiel believes that each moment in business happens only once.

The next Bill Gates will not build an operating system. The next Larry Page or Sergey Brin won’t make a search engine. And the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t create a social network. If you are copying these guys, you aren’t learning from them.

Of course, it’s easier to copy a model than to make something new. Doing what we already know how to do takes the world from 1 to n, adding more of something familiar. But every time we create something new, we go from 0 to 1. The act of creation is singular, as is the moment of creation, and the result is something fresh and strange.

2. There is no formula for innovation.

The paradox of teaching entrepreneurship is that such a formula (for innovation) cannot exist; because every innovation is new and unique, no authority can prescribe in concrete terms how to be more innovative. Indeed, the single most powerful pattern I have noticed is that successful people find value in unexpected places, and they do this by thinking about business from first principles instead of formulas.

3. The best interview question you can ask.

Whenever I interview someone for a job, I like to ask this question: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?"

This is a question that sounds easy because it’s straightforward. Actually, it’s very hard to answer. It’s intellectually difficult because the knowledge that everyone is taught in school is by definition agreed upon. And it’s psychologically difficult because anyone trying to answer must say something she knows to be unpopular. Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.

Most commonly, I hear answers like the following:

“Our educational system is broken and urgently needs to be fixed."

“America is exceptional."

“There is no God."

These are bad answers. The first and the second statements might be true, but many people already agree with them. The third statement simply takes one side in a familiar debate. A good answer takes the following form: “Most people believe in x, but the truth is the opposite of x."

What does this have to do with the future?

In the most minimal sense, the future is simply the set of all moments yet to come. But what makes the future distinctive and important isn’t that it hasn’t happened yet, but rather that it will be a time when the world looks different from today. … Most answers to the contrarian questions are different ways of seeing the present; good answers are as close as we can come to looking into the future.

4. A new company’s most important strength

Properly defined, a startup is the largest group of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future. A new company’s most important strength is new thinking: even more important than nimbleness, small size affords space to think.

5. The first step to thinking clearly

Our contrarian question – What important truth do very few people agree with you on? — is difficult to answer directly. It may be easier to start with a preliminary: what does everybody agree on?"

“Madness is rare in individuals

—but in groups, parties, nations and ages it is the rule."

— Nietzche (before he went mad)

If you can identify a delusional popular belief, you can find what lies hidden behind it: the contrarian truth.

[…]

Conventional beliefs only ever come to appear arbitrary and wrong in retrospect; whenever one collapses we call the old belief a bubble, but the distortions caused by bubbles don’t disappear when they pop. The internet bubble of the ‘90s was the biggest of the last two decades, and the lessons learned afterward define and distort almost all thinking about technology today. The first step to thinking clearly is to question what we think we know about the past.

Here is an example Thiel gives to help illuminate this idea.

The entrepreneurs who stuck with Silicon Valley learned four big lessons from the dot-com crash that still guide business thinking today:

1. Make incremental advances — “Grand visions inflated the bubble, so they should not be indulged. Anyone who claims to be able to do something great is suspect, and anyone who wants to change the world should be more humble. Small, incremental steps are the only safe path forward."

2. Stay lean and flexible — “All companies must be lean, which is code for unplanned. You should not know what your business will do; planning is arrogant and inflexible. Instead you should try things out, iterate, and treat entrepreneurship as agnostic experimentation."

3. Improve on the competition — “Don’t try to create a new market prematurely. The only way to know that you have a real business is to start with an already existing customer, so you should build your company by improving on recognizable products already offered by successful competitors."

4. Focus on product, not sales — “If your product requires advertising or salespeople to sell it, it’s not good enough: technology is primarily about product development, not distribution. Bubble-era advertising was obviously wasteful, so the only sustainable growth is viral growth."

These lessons have become dogma in the startup world; those who would ignore them are presumed to invite the justified doom visited upon technology in the great crash of 2000. And yet the opposite principles are probably more correct.

1. It is better to risk boldness than triviality.

2. A bad plan is better than no plan.

3. Competitive markets destroy profits.

4. Sales matters just as much as product."To build the future we need to challenge the dogmas that shape our view of the past. That doesn’t mean the opposite of what is believed is necessarily true, it means that you need to rethink what is and is not true and determine how that shapes how we see the world today. As Thiel says, “The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.

6. Progress comes from monopoly, not competition.

The problem with a competitive business goes beyond lack of profits. Imagine you’re running one of those restaurants in Mountain View. You’re not that different from dozens of your competitors, so you’ve got to fight hard to survive. If you offer affordable food with low margins, you can probably pay employees only minimum wage. And you’ll need to squeeze out every efficiency: That is why small restaurants put Grandma to work at the register and make the kids wash dishes in the back.

A monopoly like Google is different. Since it doesn’t have to worry about competing with anyone, it has wider latitude to care about its workers, its products and its impact on the wider world. Google’s motto—"Don’t be evil"—is in part a branding ploy, but it is also characteristic of a kind of business that is successful enough to take ethics seriously without jeopardizing its own existence. In business, money is either an important thing or it is everything. Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money; non-monopolists can’t. In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today’s margins that it can’t possibly plan for a long-term future. Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits.

So a monopoly is good for everyone on the inside, but what about everyone on the outside? Do outsize profits come at the expense of the rest of society? Actually, yes: Profits come out of customers’ wallets, and monopolies deserve their bad reputation—but only in a world where nothing changes.

In a static world, a monopolist is just a rent collector. If you corner the market for something, you can jack up the price; others will have no choice but to buy from you. Think of the famous board game: Deeds are shuffled around from player to player, but the board never changes. There is no way to win by inventing a better kind of real-estate development. The relative values of the properties are fixed for all time, so all you can do is try to buy them up.

But the world we live in is dynamic: We can invent new and better things. Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world. Creative monopolies aren’t just good for the rest of society; they’re powerful engines for making it better.

7. Rivalry causes us to overemphasize old opportunities and slavishly copy what has worked in the past.

Marx and Shakespeare provide two models that we can use to understand almost every kind of conflict.

According to Marx, people fight because they are different. The proletariat fights the bourgeoisie because they have completely different ideas and goals (generated, for Marx, by their very different material circumstances). The greater the difference, the greater the conflict.

To Shakespeare, by contrast, all combatants look more or less alike. It’s not at all clear why they should be fighting since they have nothing to fight about. Consider the opening to Romeo and Juliet: “Two households, both alike in dignity." The two houses are alike, yet they hate each other. They grow even more similar as the feud escalates. Eventually, they lose sight of why they started fighting in the first place."

In the world of business, at least, Shakespeare proves the superior guide. Inside a firm, people become obsessed with their competitors for career advancement. Then the firms themselves become obsessed with their competitors in the marketplace. Amid all the human drama, people lose sight of what matters and focus on their rivals instead.

[…]

Rivalry causes us to overemphasize old opportunities and slavishly copy what has worked in the past.

8. Last can be first

You’ve probably heard about “first mover advantage": if you’re the first entrant into a market, you can capture significant market share while competitors scramble to get started. That can work, but moving first is a tactic, not a goal. What really matters is generating cash flows in the future, so being the first mover doesn’t do you any good if someone else comes along and unseats you. It’s much better to be the last mover – that is, to make the last great development in a specific market and enjoy years or even decades of monopoly profits.

Grandmaster José Raúl Capablanca put it well: to succeed, “you must study the endgame before everything else."

Zero to One is full of counterintuitive insights that will help your thinking and ignite possibility.

(image source)

Filed Under: Books, Business, Creativity, Critical Thinking, Culture, Innovation, Peter Thiel

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

A System for Remembering What you Read

A System for Remembering What you Read

Last year, I read 161 books cover-to-cover. And that doesn’t include the ones that I started to read and put down. I learned a lot in the process about what works and what doesn’t work. I get asked a lot how I remember what I read.

I have a system that I use for non-fiction books that enables me to remember quite a bit. And when I can’t remember I generally know where to look to find the answers.

Here are some of the tips that work for me:

- Learn How to Read A Book.

- Start with the index, table of contents, and the preface. This will give you a good sense of the book.

- Be ok with deciding now is not the time to read the book.

- Read one book at a time.

- Put it down if you lose interest.

- Mark up the book while reading it. Questions. Thoughts. And, more importantly, connections to other ideas.

- At the end of each chapter, without looking back, write some notes on the main points/arguments/take-aways. Then look back through the chapter and put anything down you missed.

- Specifically note anything that was in the chapter that you can apply somewhere else.

- When you’re done the book, take out a blank sheet of paper and explain the core ideas/arguments of the book to yourself. Where you have problems, go back and review your notes. This is the Feynman Technique.

- Put the book down for a week.

- Pick the book back up, re-read all of your notes/highlights/marginalia/etc. Time is a good filter – what’s still important? Note this in the inside of the cover with a reference to the page number.

- Put the notes that you want to keep in your common place book/resource.

But one thing that most people don’t appreciate enough is that what you read makes a huge difference for how well you remember things.

We fail to remember a lot of the stuff we read because it’s not building on any existing knowledge. We’re often trying to learn complex things (that change rapidly) without understanding the basic things (which change slowly or not at all). Or, worse still, we’re uncritically letting other people do the thinking for us. This is the adult equivalent of regurgitating the definition of a bolded word in our high school textbook.

Both of these lead to the illusion of knowledge and overconfidence.

I’d argue that a better approach is to build a latticework of Mental Models. That is, acquire the core multi-disciplinary knowledge and use that as your foundation. This is the best investment because this stuff doesn’t change and if it does it changes really slowly. This becomes your foundation. This is what you build on. So when you read and connect things to the core knowledge, not only do you have a better idea of how things fit together but you strengthen those connections in your head from use.

If you’re looking to acquire worldly wisdom, time is your best filter. It makes sense to focus on learning the core ideas over multiple disciplines. These remain constant. And when you have a solid foundation it’s easier to build upon because you connect what you’re learning to the (now very solid) foundation.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son

Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son

With wisdom and lessons seeping off every page, Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son is a must read. The letters, from John Graham, Head of the House of Graham & Company, to his son Pierrepont were collected and bound by American Journalist George Horace Lorimer in the early 1900s. The Letters were quite well known in the early 20th century. I’m not sure why they are not well known today, but they should be.

***

Writing to his son, Pierrepont, at Harvard University, a Freshman, Graham offers advice on the eduction he is about to receive inside and outside of the classroom.

What we’re really sending you to Harvard for is to get a little of the education that’s so good and plenty there. When it’s passed around you don’t want to be bashful, but reach right out and take a big helping every time, for I want you to get your share. You’ll find that education’s about the only thing lying around loose in this world, and that it’s about the only thing a fellow can have as much of as he’s willing to haul away. Everything else is screwed down tight and the screw-driver lost.

…

Some men learn the value of money by not having any and starting out to pry a few dollars loose from the odd millions that are lying around; and some learn it by having fifty thousand or so left to them and starting out to spend it as if it were fifty thousand a year. Some men learn the value of truth by having to do business with liars; and some by going to Sunday School. Some men learn the cussedness of whiskey by having a drunken father; and some by having a good mother. Some men get an education from other men and newspapers and public libraries; and some get it from professors and parchments—it doesn’t make any special difference how you get a half-nelson on the right thing, just so you get it and freeze on to it.

…

The first thing that any education ought to give a man is character, and the second thing is education. That is where I’m a little skittish about this college business. I’m not starting in to preach to you, because I know a young fellow with the right sort of stuff in him preaches to himself harder than any one else can, and that he’s mighty often switched off the right path by having it pointed out to him in the wrong way.

…

There are two parts of a college education—the part that you get in the schoolroom from the professors, and the part that you get outside of it from the boys. That’s the really important part. For the first can only make you a scholar, while the second can make you a man.

Education’s a good deal like eating—a fellow can’t always tell which particular thing did him good, but he can usually tell which one did him harm.

…

Does a College education pay? … You bet it pays. Anything that trains a boy to think and to think quick pays; anything that teaches a boy to get the answer before the other fellow gets through biting the pencil, pays.

College doesn’t make fools; it develops them. It doesn’t make bright men; it develops them. A fool will turn out a fool, whether he goes to college or not, though he’ll probably turn out a different sort of a fool. And a good, strong boy will turn out a bright, strong man whether he’s worn smooth in the grab-what-you-want-and-eat-standing-with-one-eye-skinned-for-the-dog school of the streets and stores, or polished up and slicked down in the give-your-order-to-the-waiter-and-get-a-sixteen-course-dinner school of the professors. But while the lack of a college education can’t keep No. 1 down, having it boosts No. 2 up.

…

Of course, some men are like pigs, the more you educate them, the more amusing little cusses they become, and the funnier capers they cut when they show off their tricks. Naturally, the place to send a boy of that breed is to the circus, not to college.…

… it isn’t so much knowing a whole lot, as knowing a little and how to use it that counts.

***

When Pierrepont—still at Harvard—submits his expense account to his father, he receives some plain-spoken advice to smarten up.

I have noticed for the last two years that your accounts have been growing heavier every month, but I haven’t seen any signs of your taking honors to justify the increased operating expenses; and that is bad business—a good deal like feeding his weight in corn to a scalawag steer that won’t fat up.

…

The sooner you adjust your spending to what your earning capacity will be, the easier they will find it to live together.

The only sure way that a man can get rich quick is to have it given to him or to inherit it. You are not going to get rich that way—at least, not until after you have proved your ability to hold a pretty important position with the firm; and, of course, there is just one place from which a man can start for that position with Graham & Co. It doesn’t make any difference whether he is the son of the old man or of the cellar boss—that place is the bottom. And the bottom in the office end of this business is a seat at the mailing-desk, with eight dollars every Saturday night.

I can’t hand out any ready-made success to you. It would do you no good, and it would do the house harm. There is plenty of room at the top here, but there is no elevator in the building. Starting, as you do, with a good education, you should be able to climb quicker than the fellow who hasn’t got it; but there’s going to be a time when you begin at the factory when you won’t be able to lick stamps so fast as the other boys at the desk. Yet the man who hasn’t licked stamps isn’t fit to write letters. Naturally, that is the time when knowing whether the pie comes before the ice-cream, and how to run an automobile isn’t going to be of any real use to you.

I simply mention these things because I am afraid your ideas as to the basis on which you are coming with the house have swelled up a little in the East. I can give you a start, but after that you will have to dynamite your way to the front by yourself.

…

You know how I began—I was started off with a kick, but that proved a kick up, and in the end every one since has lifted me a little bit higher. I got two dollars a week, and slept under the counter, and you can bet I knew just how many pennies there were in each of those dollars, and how hard the floor was. That is what you have got to learn.

…

The Bills ain’t all in the butcher business. I’ve got some of them right now in my office, but they will never climb over the railing that separates the clerks from the executives. Yet if they would put in half the time thinking for the house that they give up to hatching out reasons why they ought to be allowed to overdraw their salary accounts, I couldn’t keep them out of our private offices with a pole-ax, and I wouldn’t want to; for they could double their salaries and my profits in a year. But I always lay it down as a safe proposition that the fellow who has to break open the baby’s bank toward the last of the week for car-fare isn’t going to be any Russell Sage when it comes to trading with the old man’s money. He’d punch my bank account as full of holes as a carload of wild Texans would a fool stockman that they’d got in a corner.

Now I know you’ll say that I don’t understand how it is; that you’ve got to do as the other fellows do; and that things have changed since I was a boy. There’s nothing in it. Adam invented all the different ways in which a young man can make a fool of himself, and the college yell at the end of them is just a frill that doesn’t change essentials. The boy who does anything just because the other fellows do it is apt to scratch a poor man’s back all his life. He’s the chap that’s buying wheat at ninety-seven cents the day before the market breaks. They call him “the country" in the market reports, but the city’s full of him. It’s the fellow who has the spunk to think and act for himself, and sells short when prices hit the high C and the house is standing on its hind legs yelling for more, that sits in the directors’ meetings when he gets on toward forty.

…

There are times when it’s safest to be lonesome. Use a little common-sense, caution and conscience. You can stock a store with those three commodities, when you get enough of them. But you’ve got to begin getting them young. They ain’t catching after you toughen up a bit.

You needn’t write me if you feel yourself getting them. The symptoms will show in your expense account. Good-by; life’s too short to write letters and New York’s calling me on the wire.

***

Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son contains 20 letters of practical advice for parents— looking for some no nonsense advice on raising children—and wisdom seekers alike. This is one of the best books you’ve never heard about.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Albert Einstein on Sifting the Essential from the Non-Essential

Albert Einstein on Sifting the Essential from the Non-Essential

Charlie Munger once said: “We have a passion for keeping things simple."

Einstein says, “I soon learned to scent out what was able to lead to fundamentals and to turn aside from everything else, from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind." Most of us try to consume more information, thinking it will lead to more signal, without thinking about how we filter and how we process the information coming in.

Knowing some basic principles helps as does knowing how to combine them. As Einstein says “A theory is the more impressive the greater the simplicity of its premises, the more different kinds of things it relates, and the more extended its area of applicability."

It wasn’t because he understood more about the complicated than other people, as John Wheeler points out in his short biographical memoir on Einstein:

Many a man in the street thinks of Einstein as a man who could only make headway in his work by dint of pages of complicated mathematics; the truth is the direct opposite. As Hilbert put it, “Every boy in the streets of our mathematical Gottingen understands more about four-dimensional geometry than Einstein. Yet, despite that, Einstein did the work and not the mathematicians." Time and again, in the photoelectric effect, in relativity, in gravitation, the amateur grasped the simple point that had eluded the expert.

Where did Einstein acquire this ability to sift the essential from the non-essential? For this we turn to his first job.

In the view of many, the position of clerk of the Swiss patent office was no proper job at all, but it was the best job available to anyone with (Einstein’s) unpromising university record. He served in the Bern office for seven years, from June 23, 1902 to July 6, 1909. Every morning he faced his quote of patent applications. Those were the days when a patent application had to be accompanied by a working model. Over and above the applications and the models was the boss, a kind man, a strict man, a wise man. He gave strict instructions: explain very briefly, if possible in a single sentence, why the device will work or why it won’t; why the application should be granted or why it should be denied.

Day after day Einstein had to distill the central lesson out of objects of the greatest variety that man has power to invent. Who knows a more marvelous way to acquire a sense of what physics is and how it works? It is no wonder that Einstein always delighted in the machinery of the physical world—from the action of a compass needle to the meandering of a river, and from the perversities of a gyroscope to the drive of Flettner’s rotor ship.

Who else but a patent clerk could have discovered the theory of relativity? “Who else," Wheeler writes, “could have distilled this simple central point from all the clutter of electromagnetism than someone whose job it was over and over to extract simplicity out of complexity."

Charles Munger speaks to the importance of sifting folly.

Part of that (possessing uncommon sense), I think, is being able to tune out folly, as distinguished from recognizing wisdom. You’ve got whole categories of things you just bat away so your brain isn’t cluttered with them. That way, you’re better able to pick up a few sensible things to do.

Filed Under: Albert Einstein, Charlie Munger, Culture, Information, Simplicity, Too much information

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

The Best Articles on Farnam Street

Best Articles

Knowing where to start can be a little difficult.

To help, I’ve compiled a list of the best articles based on popularity, feedback I’ve received, or impact on people’s lives.

Best Articles by Category

Mental Models/Thinking

Mental Models — The best place to start to understand mental models.

Adding Mental Models to Your Mind’s Toolbox — How mental models are useful and how we can prioritize them.

How to Think — Thinking about how we think.

Changing How We Think — “To change patterns of thinking, change patterns of talking."

Herbert Simon on using Mental Models — What would we see if we cracked open the brain of a decision-maker?

Richard Feynman: The Difference Between Knowing the Name of Something and Knowing Something — Just because you know what something is called does not mean you understand it.

Albert Einstein on Sifting the Essential from the Non-Essential — “I soon learned to scent out what was able to lead to fundamentals and to turn aside from everything else, from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind."

The Work Required To Have An Opinion — “I never allow myself to have an opinion on anything that I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do."

Charlie Munger on the Value of Thinking Backward and Forward — “Flipping one’s thinking both forward and backward is a powerful sort of mental trickery that will help improve your thinking."

Charlie Munger’s Five Simple Notions to Help Solve Big Problems — The five big, but simple notions Charlie Munger finds useful to begin solving a complex problem.

Carol Dweck: The Two Mindsets And The Power of Believing That You Can Improve — Dweck’s work shows the power of our most basic beliefs. Whether conscious or subconscious, they strongly “affect what we want and whether we succeed in getting it." Much of what we think we understand of our personality comes from our “mindset." This both propels us and prevents us from fulfilling our potential.

How did Charles Darwin Become an Effective Thinker? Follow the Golden Rule — Darwin’s habit of forced objectivity helped him see reality clearly, even though he wasn’t nearly the smartest person of his time.

Decision Making

Avoiding Stupidity is Easier than Seeking Brilliance — If you’re an amateur your focus should be on avoiding stupidity.

How We Can Improve Our Decisions — My keynote speech at the Pender Investment Conference.

Decisions Under Uncertainty — We often think we’re making decisions involving risk when really we’re dealing with uncertainty.

How Using a Decision Journal can Help you Make Better Decisions — “Odds are you’re going to discover two things. First, you’re right a lot of the time. Second, it’s often for the wrong reasons."

Daniel Kahneman’s Favorite Approach For Making Better Decisions — The premortem.

Your Environment Matters If You Want To Make Better Decisions — It’s hard to make rational decisions the way most of us work.

What You Can Learn About Making Better Decisions From One of Baseball’s Greatest Hitters — “the single most important thing for a hitter was to get a good ball to hit."

A Two-Step Process For Making Effective Decisions — “One approach is rationality-the way you’d work out a bridge problem: by evaluating the real interests, the real probabilities and so forth. And the other is to evaluate the psychological factors that cause subconscious conclusions-many of which are wrong."

How to Make Better Decisions In Life And Work — Most of us rarely use a process for thinking about things. If we do use one it’s likely to be the pros-and-cons list. While better than nothing, this approach is still deeply flawed because it doesn’t really account for biases.

What Matters More in Decisions: Analysis or Process? — “Our research indicates that, contrary to what one might assume, good analysis in the hands of managers who have good judgment won’t naturally yield good decisions."

Making Smart Choices — “We have found that even the most complex decision can be analysed and resolved by considering a set of eight elements. The first five—Problem, Objectives, Alternatives, Consequences, and Tradeoffs—constitute the core of our approach and are applicable to virtually any decision."

What happens when decisions go wrong? — “When a decision goes awry, we tend to focus on the people who made it, rather than on the decision itself. Our assumption, which is really unwarranted, is that good people make good decisions, and vise versa."

Innovation

Seneca on Gathering Ideas And Combinatorial Creativity — “We should follow, men say, the example of the bees, who flit about and cull the flowers that are suitable for producing honey, and then arrange and assort in their cells all that they have brought in; these bees, as our Vergil says,"

Steve Jobs on Creativity — “Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things."

How to be Creative — A great short video.

Building Blocks and Innovation — Most innovation comes from combining well-known, well-established, building blocks in new ways.

A Technique for Producing Ideas — “the habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas."

The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights — A lot of people aren’t wrestling with a problem when they come up with an accidental insight.

Why Your Organization Sucks at Innovating — It’s easy to make your organization more innovative if you stop trying to show everyone how innovative you are.

The Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators — The ability to look at problems in a non-standard way might be the most sought after competency of the future.

Seven Innovation Myths — Myth #1: Innovation is about the latest thing.

Einstein on The Essential Feature of Productive Thought — “Combinatory play seems to be the essential feature in productive thought."

Eight Things I Learned from Peter Thiel’s Zero To One — There is no formula to innovation.

Google and Combinatorial Innovation — How a solution for porn developed into so much more.

Innovation: The Attacker’s Advantage — What if tomorrow does not resemble today?

Creativity and the Necessity of Giving up Your Best Loved Ideas and Starting Over Again — “All we can hope is that we will fail better. That we won’t succumb to fear of the unknown. That we will not fall prey to the easy enchantments of repeating what may have worked in the past."

Leadership

16 Leadership Lessons from a Four Star General — “We like to equate leaders with values we admire, but the two can be separate and distinct."

10 Life Lessons From a Navy SEAL — “If you want to change the world sometimes you have to slide down the obstacle head first."

The Unwritten Rules of Management — “#1. Learn to say, ‘I don’t know.’ If used when appropriate, it will be often."

Warren Buffett: The three things I look for in a person — “Inevitably, the most useful qualities have nothing to do with IQ, grades, or family connections."

Leadership Is a Gift Given by Those Who Follow — “Leadership is a gift. It’s given by those who follow. You have to be worthy of it."

Culture Eats Strategy: Nucor’s Ken Inverson on Building a Different Kind of Company — “Steel is about as bad a business as you could invent. Yet in Ken Iverson’s 30+ year reign, Nucor compounded its per-share earnings at a rate of about 17% per annum. There must have been something going on here."

Letters

Richard Feynman’s Love Letter to His Wife Sixteen Months After Her Death — This will touch your soul.

Charles Bukowski: An Argument Against Censorship — “The thing that I fear discriminating against is humor and truth."

Hunter S. Thompson on Finding Your Purpose and Living a Meaningful Life — You won’t find better advice. Anywhere.

Eudora Welty to The New Yorker: The best job application ever — “I suppose you’d be more interested in even a sleight-o’-hand trick than you’d be in an application for a position with your magazine, but as usual you can’t have the thing you want most."

Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son — “College doesn’t make fools; it develops them. It doesn’t make bright men; it develops them. A fool will turn out a fool, whether he goes to college or not, though he’ll probably turn out a different sort of a fool."

F. Scott Fitzgerald offers a list of things to worry about and things not to worry about — Offering a hint of his parenting, the letter from August 1933 concludes with a list of things to worry about and things not to worry about.

Richard Feynman’s Letter on What Problems to Solve — “With you I made a mistake, I gave you the problem instead of letting you find your own."

Reading

How To Read A Book — Seriously.

The Top 3 Most Effective Ways to Take Notes While Reading — This is how I take notes.

A System For Remembering What you Read — A helpful reading system you can implement today.

Twenty-Five Pages a Day – How to get the Big Books read.

The Buffett Formula: How To Get Smarter — The simple (but not easy) way to acquire wisdom.

Other

Ten Techniques for Building Quick Rapport With Anyone — Warning: the content in this post is so effective that I encourage you to think carefully how it is used. I do not endorse or condone the use of these skills in malicious or deceptive ways.

Mistakes — Just because we’ve lost our way doesn’t mean that we are lost forever. In the end, it’s not the failures that define us so much as how we respond.

How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big — Goals are for losers, passion is bullshit, and mediocre skills can make you valuable.

Tiny Beautiful Things — “Don’t lament so much about how your career is going to turn out. You don’t have a career."

David Ogilvy 10 Tips on Writing — In 1982, the original “Mad Man" David Ogilvy, sent the following internal memo to all employees of his advertising agency, Ogilvy & Mather, titled “How to Write."

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Richard Feynman: Knowing the Name of Something

Richard Feynman: The Difference Between Knowing the Name of Something and Knowing Something

Richard Feynman, who believed that “the world is much more interesting than any one discipline," was no ordinary genius.

His explanations — on why questions, why trains stay on the tracks as they go around a curve, how we look for new laws of science, how rubber bands work, — are simple and powerful. Even his letter writing moves you. His love letter to his wife sixteen months after her death still stirs my soul.

In this short clip (below), Feynman articulates the difference between knowing the name of something and understanding it.

See that bird? It’s a brown-throated thrush, but in Germany it’s called a halzenfugel, and in Chinese they call it a chung ling and even if you know all those names for it, you still know nothing about the bird. You only know something about people; what they call the bird. Now that thrush sings, and teaches its young to fly, and flies so many miles away during the summer across the country, and nobody knows how it finds its way.

Knowing the name of something doesn’t mean you understand it. We talk in fact-deficient, obfuscating generalities to cover up our lack of understanding.

How then should we go about learning? On this Feynman echoes Einstein, and proposes that we take things apart:

In order to talk to each other, we have to have words, and that’s all right. It’s a good idea to try to see the difference, and it’s a good idea to know when we are teaching the tools of science, such as words, and when we are teaching science itself.

[…]

There is a first grade science book which, in the first lesson of the first grade, begins in an unfortunate manner to teach science, because it starts off with the wrong idea of what science is. There is a picture of a dog–a windable toy dog–and a hand comes to the winder, and then the dog is able to move. Under the last picture, it says “What makes it move?" Later on, there is a picture of a real dog and the question, “What makes it move?" Then there is a picture of a motorbike and the question, “What makes it move?" and so on.

I thought at first they were getting ready to tell what science was going to be about–physics, biology, chemistry–but that wasn’t it. The answer was in the teacher’s edition of the book: the answer I was trying to learn is that “energy makes it move."

Now, energy is a very subtle concept. It is very, very difficult to get right. What I mean is that it is not easy to understand energy well enough to use it right, so that you can deduce something correctly using the energy idea–it is beyond the first grade. It would be equally well to say that “God makes it move," or “spirit makes it move," or “movability makes it move." (In fact, one could equally well say “energy makes it stop.")

Look at it this way: that’s only the definition of energy; it should be reversed. We might say when something can move that it has energy in it, but not what makes it move is energy. This is a very subtle difference. It’s the same with this inertia proposition.

Perhaps I can make the difference a little clearer this way: If you ask a child what makes the toy dog move, you should think about what an ordinary human being would answer. The answer is that you wound up the spring; it tries to unwind and pushes the gear around.

What a good way to begin a science course! Take apart the toy; see how it works. See the cleverness of the gears; see the ratchets. Learn something about the toy, the way the toy is put together, the ingenuity of people devising the ratchets and other things. That’s good. The question is fine. The answer is a little unfortunate, because what they were trying to do is teach a definition of what is energy. But nothing whatever is learned.

[…]

I think for lesson number one, to learn a mystic formula for answering questions is very bad.

There is a way to test whether you understand the idea or only know the definition. It’s called the Feynman Technique and it looks like this:

Test it this way: you say, “Without using the new word which you have just learned, try to rephrase what you have just learned in your own language." Without using the word “energy," tell me what you know now about the dog’s motion." You cannot. So you learned nothing about science. That may be all right. You may not want to learn something about science right away. You have to learn definitions. But for the very first lesson, is that not possibly destructive?

I think this is what Montaigne was hinting at in his Essays when he wrote:

We take other men’s knowledge and opinions upon trust; which is an idle and superficial learning. We must make them our own. We are just like a man who, needing fire, went to a neighbor’s house to fetch it, and finding a very good one there, sat down to warm himself without remembering to carry any back home. What good does it do us to have our belly full of meat if it is not digested, if it is not transformed into us, if it does not nourish and support us?

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

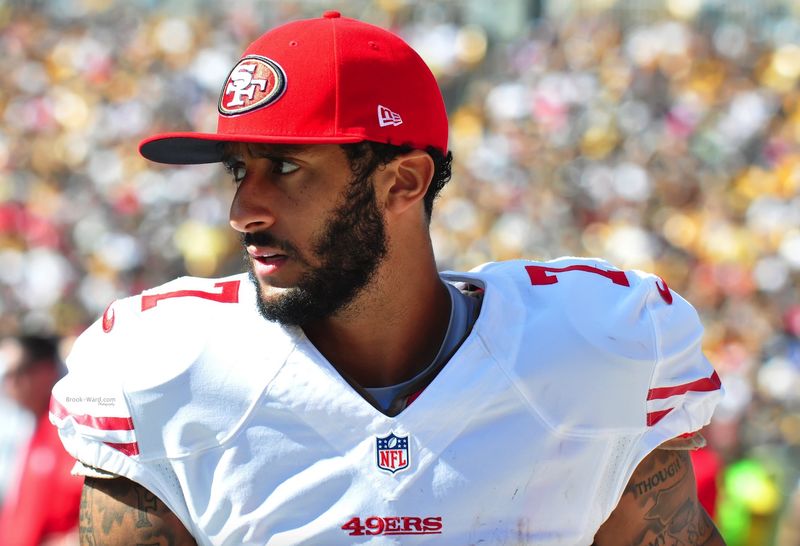

Kaepernick and Media Coverage

thearcmag.com

Kaepernick and Media Coverage

Tito Hernandez

We’ve come a long way since Charles Barkley said, “I’m not a role model."

The Colin Kaepernick incident — in which Kaepernick decided to sit during the national anthem due to the oppression experienced by African Americans and others — has caused a lot of controversy, especially among conservative critics, who believe that the embattled San Francisco 49ers quarterback is a figurehead of American citizens who dishonor the flag and the country it represents.

Consider Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who attacked President Barack Obama on Tuesday, suggesting that Obama was actually encouraging Kaepernick, a “rich, spoiled athlete" to “disrespect" the flag.

Or see The Blaze anchor Tomi Lahren, who criticized Kaepernick not once, not twice, but six times by featuring him in her Facebook-shareable “final thoughts." (A touchdown is six points — we see what you did there, Tomi.)

On the other hand, in light of sit-gate, Kaepernick has become a darling of left-leaning media, with The Nation and the New York Daily News coming to his defense, to name two outlets of many who supported Kaepernick’s actions. What conservative critics miss, according to the two outlets above, is the substance of Kaepernick’s critique, which focuses on the mistreatment African Americans (and other people of color) endure at the hands of a law and order superstructure which oppresses them at various points. Kaepernick alludes to police brutality, but the criticism can extend to the mass incarceration of African Americans facilitated by a prison-industrial system designed to achieve those results.

“There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder," Kaepernick said before a preseason loss against the Green Bay Packers on August 26.

Kaepernick has received praise for sitting during the national anthem, a decision at odds with other athletes who, when faced with the opportunity to comment on socially significant conversations, tend to opt out as quickly as possible. There are few aspects to Michael Jordan’s legacy we might call ignominious, but his “silence" during his playing days is considered one of them. Jordan himself penned an essay for ESPN’s The Undefeated, lamenting over his failure to speak out in the past and suggesting that he can no longer stay silent.

Yet Kaepernick has not been the only athlete to speak out social issues; he is, however, one of the few whose actions and comments have generated lots of attention.

Benjamin Watson is a tight end who plays for the Baltimore Ravens, although he won’t feature this season due to suffering a torn Achilles tendon which ended his season on August 27. Watson has been speaking out about the mistreatment of African Americans since the Michael Brown police-realted shooting in Ferguson, Missouri caused protests to erupt in the city’s streets for months. He wrote an essay on the issue on his Facebook account, while also speaking up for religious freedom and offering his view that America is no longer a Christian nation.

But when Watson chose to address the issue of abortion, saying on August 7 that the “the idea with Planned Parenthood and [Margaret] Sanger in the past was to exterminate blacks," his comments barely received any media attention.

“It’s like when black girls are pregnant, it’s like a statistic, but when white girls get pregnant, they get a TV show," Watson said during his interview with the Turning Point Pregnancy Resource Center.

A simple Google search reveals that the only major media coverage this story received was from CBS Sports. It’s almost as if his words were never uttered.

The question is: Who gets to decide which story is a worthy social justice cause?

African Americans make up 12.6% of the United States population, according to 2010 census data, while the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that black women accounted for 35.4% of U.S. abortions in 2009. Data from The Guttmacher Institute shows that Hispanic women accounted for 25% of U.S. abortions in 2008, although Hispanics made up 16.3% of the U.S. population. In 2008, the total number of abortions was 1,212,350.

When it comes to the issue of police-related killings, ThinkProgress concludes that in 2015, 1,186 people were killed by police.

Looking purely at the numbers, shouldn’t the issue Watson has chosen to shine a light on get more media play?

Sometimes it is thought that bias involves skewing a story in a particular direction. That’s not under dispute. But there’s another kind of bias, less perceptible but arguably more intellectually destructive, which occurs when the media underreports or flat out fails to report on matters deemed morally insignificant according to the ideological preferences of those who populate the field. This, too, is bias.

Benjamin Watson is a black man speaking out against racial oppression from police brutality as well as from abortion.

But his commentary on abortion went ignored.

The advent of conservative media is thus not a mystery. When mainstream outlets don’t just slant coverage but make coverage-selection decisions that result in the underreporting of issues meaningful to conservatives, it’s no wonder a market emerges for coverage aligned with conservative priorities. To be sure, this has led to all manner of hackery on the right — What I’m arguing, though, is that this is largely brought on by the failure of left-leaning media to, for example, deem Benjamin Watson’s comments worthy of reflection.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016