Meditation for Beginners: 20 Practical Tips for Understanding the Mind : zen habits

Meditation for Beginners: 20 Practical Tips for Understanding the Mind

By Leo Babauta

The most important habit I’ve formed in the last 10 years of forming habits is meditation. Hands down, bar none.

Meditation has helped me to form all my other habits, it’s helped me to become more peaceful, more focused, less worried about discomfort, more appreciative and attentive to everything in my life. I’m far from perfect, but it has helped me come a long way.

Probably most importantly, it has helped me understand my own mind. Before I started meditating, I never thought about what was going on inside my head — it would just happen, and I would follow its commands like an automaton. These days, all of that still happens, but more and more, I am aware of what’s going on. I can make a choice about whether to follow the commands. I understand myself better (not completely, but better), and that has given me increased flexibility and freedom.

So … I highly recommend this habit. And while I’m not saying it’s easy, you can start small and get better and better as you practice. Don’t expect to be good at first — that’s why it’s called “practice"!

These tips aren’t aimed at helping you to become an expert … they should help you get started and keep going. You don’t have to implement them all at once — try a few, come back to this article, try one or two more.

- Sit for just two minutes. This will seem ridiculously easy, to just meditate for two minutes. That’s perfect. Start with just two minutes a day for a week. If that goes well, increase by another two minutes and do that for a week. If all goes well, by increasing just a little at a time, you’ll be meditating for 10 minutes a day in the 2nd month, which is amazing! But start small first.

- Do it first thing each morning. It’s easy to say, “I’ll meditate every day," but then forget to do it. Instead, set a reminder for every morning when you get up, and put a note that says “meditate" somewhere where you’ll see it.

- Don’t get caught up in the how — just do. Most people worry about where to sit, how to sit, what cushion to use … this is all nice, but it’s not that important to get started. Start just by sitting on a chair, or on your couch. Or on your bed. If you’re comfortable on the ground, sit cross-legged. It’s just for two minutes at first anyway, so just sit. Later you can worry about optimizing it so you’ll be comfortable for longer, but in the beginning it doesn’t matter much, just sit somewhere quiet and comfortable.

- Check in with how you’re feeling. As you first settle into your meditation session, simply check to see how you’re feeling. How does your body feel? What is the quality of your mind? Busy? Tired? Anxious? See whatever you’re bringing to this meditation session as completely OK.

- Count your breaths. Now that you’re settled in, turn your attention to your breath. Just place the attention on your breath as it comes in, and follow it through your nose all the way down to your lungs. Try counting “one" as you take in the first breath, then “two" as you breathe out. Repeat this to the count of 10, then start again at one.

- Come back when you wander. Your mind will wander. This is an almost absolute certainty. There’s no problem with that. When you notice your mind wandering, smile, and simply gently return to your breath. Count “one" again, and start over. You might feel a little frustration, but it’s perfectly OK to not stay focused, we all do it. This is the practice, and you won’t be good at it for a little while.

- Develop a loving attitude. When you notice thoughts and feelings arising during meditation, as they will, look at them with a friendly attitude. See them as friends, not intruders or enemies. They are a part of you, though not all of you. Be friendly and not harsh.

- Don’t worry too much that you’re doing it wrong. You will worry you’re doing it wrong. That’s OK, we all do. You’re not doing it wrong. There’s no perfect way to do it, just be happy you’re doing it.

- Don’t worry about clearing the mind. Lots of people think meditation is about clearing your mind, or stopping all thoughts. It’s not. This can sometimes happen, but it’s not the “goal" of meditation. If you have thoughts, that’s normal. We all do. Our brains are thought factories, and we can’t just shut them down. Instead, just try to practice focusing your attention, and practice some more when your mind wanders.

- Stay with whatever arises. When thoughts or feelings arise, and they will, you might try staying with them awhile. Yes, I know I said to return to the breath, but after you practice that for a week, you might also try staying with a thought or feeling that arises. We tend to want to avoid feelings like frustration, anger, anxiety … but an amazingly useful meditation practice is to stay with the feeling for awhile. Just stay, and be curious.

- Get to know yourself. This practice isn’t just about focusing your attention, it’s about learning how your mind works. What’s going on inside there? It’s murky, but by watching your mind wander, get frustrated, avoid difficult feelings … you can start to understand yourself.

- Become friends with yourself. As you get to know yourself, do it with a friendly attitude instead of one of criticism. You’re getting to know a friend. Smile and give yourself love.

- Do a body scan. Another thing you can do, once you become a little better at following your breath, is focus your attention on one body part at a time. Start at the soles of your feet — how do those feel? Slowly move to your toes, the tops of your feet, your ankles, all the way to the top of your head.

- Notice the light, sounds, energy. Another place to put your attention, again, after you’ve practice with your breath for at least a week, is the light all around you. Just keep your eyes on one spot, and notice the light in the room you’re in. Another day, just focus on noticing sounds. Another day, try to notice the energy in the room all around you (including light and sounds).

- Really commit yourself. Don’t just say, “Sure, I’ll try this for a couple days." Really commit yourself to this. In your mind, be locked in, for at least a month.

- You can do it anywhere. If you’re traveling or something comes up in the morning, you can do meditation in your office. In the park. During your commute. As you walk somewhere. Sitting meditation is the best place to start, but in truth, you’re practicing for this kind of mindfulness in your entire life.

- Follow guided meditation. If it helps, you can try following guided meditations to start with. My wife is using Tara Brach’s guided meditations, and she finds them very helpful.

- Check in with friends. While I like meditating alone, you can do it with your spouse or child or a friend. Or just make a commitment with a friend to check in every morning after meditation. It might help you stick with it for longer.

- Find a community. Even better, find a community of people who are meditating and join them. This might be a Zen or Tibetan community near you (for example), where you go and meditate with them. Or find an online group and check in with them and ask questions, get support, encourage others. My Sea Change Program has a community like that.

- Smile when you’re done. When you’re finished with your two minutes, smile. Be grateful that you had this time to yourself, that you stuck with your commitment, that you showed yourself that you’re trustworthy, where you took the time to get to know yourself and make friends with yourself. That’s an amazing two minutes of your life.

Meditation isn’t always easy or even peaceful. But it has truly amazing benefits, and you can start today, and continue for the rest of your life.

If you’d like help with mindfulness, check out my new Zen Habits Beginner’s Guide to Mindfulness short ebook.

Posted: Friday, January 15, 2016

Previous post: Rules for Getting Organized & Decluttered

About :: Uncopyright :: Archives :: Books :: Habit Program

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

How to Become the World’s Greatest Lover : zen habits

How to Become the World’s Greatest Lover

By Leo Babauta

You reject the limitations of being a romantic Cassanova, restricted to loving only those who fall for your seductions. You want to love every one. Every single living being. Everything in this miraculous universe.

You learn to love it all, in its majestic entirety.

You don’t discriminate between the aesthetically beautiful or the squalid, the dirty, the flawed. You don’t require near perfection for your love, nor do you need people to act the way you want them to for them to receive your love.

Your love is unconditional, limitless, all-pervasive. It cares not about political differences, ethnic differences, gender, wealth status, fame, achievement, body shape, education level, religious beliefs. It loves every person, because they are all deserving of love. Your love reaches every living being, including animals, because they deserve love. Your love spreads to plants, mountain ranges, galaxies, as all part of one ever-changing, fluid energy.

This doesn’t happen every second of every day. In fact, it happens in fleeting moments, and then you return to your self-centered concerns. But for that fleeting moment, you are the World’s Greatest Lover.

So what? Who cares about a title like that? The title doesn’t matter, but being able to love like that changes you. For that evanescent moment, you feel that love completely, and are therefore lifted out of your petty concerns about what people think of you, whether you’re doing something right, whether you’re missing out. You are elevated above your usual limitations, and all of a sudden you are happy. You are at peace with the world, and want nothing but everyone’s happiness.

You also see that other people are suffering, in similar ways to how you’re suffering, and you have a genuine, whole-hearted wish for their suffering to end.

And so those brief moments of pure love are powerful. And worthy of trying to get to, over and over again.

To find these moments of love, you train your mind:

- You meditate every day.

- In meditation, you see the way your mind works.

- You see the ways your mind avoids discomfort and habitually runs to comfort.

- You learn to stay with discomfort, and find that pain and frustration are not unbearable.

- You train yourself to see others as going through the same things you’re going through.

- You train yourself to see yourself as not solid, but fluid.

- You train yourself to see everything else as fluid and changing as well, not static but dynamic.

- You learn to find happiness in your connection to everything else, in seeing the fluid nature of the moment.

- You train yourself to meditate on the wish for others to be happy.

- You train yourself to not judge things as “good" or “bad" but simply be curious about them.

- You start to accept others as they are, love them for their flaws and uniqueness.

And this practice doesn’t come overnight, but in small steps. It is messy and full of uncertainty. That’s OK, because uncertainty is exactly what you’re learning to work with.

This practice helps you overcome fear and self-doubt and uncertainty. It helps you overcome all the limitations that have sabotaged your attempts at habit change, that have held you back because of fear, that make you stressed and frustrated each day. The practice improves your relationships, makes you happier with yourself, helps you to be more mindful, and gives you inspiration to do your best work.

When you find out how to become the World’s Greatest Lover, of course, you want to help others do the same. That’s part of the love.

Whole-Hearted Living Course

I can’t promise to make you the World’s Greatest Lover, but I can say that we’ll explore all of these things in my new course — Whole-Hearted Living: Training for the Mind.

The course is starting now, and you can take it if you join my Sea Change Program.

It’s a 6-week course, with two lessons a week (mostly video lessons) and a daily meditation practice that will take just a few minutes a day. In addition, you can ask questions, do daily mindfulness challenges, join a practice team, and get email reminders.

Join Sea Change today and start learning the amazing benefits of mindfulness and compassion!

Posted: Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Previous post: Our Relationship with the Present Moment

Next post: Why We Struggle with Change

About :: Uncopyright :: Archives :: Books :: Habit Program

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Fear Is Why We Have Too Much Stuff : zen habits

Fear Is Why We Have Too Much Stuff

By Leo Babauta

While we might want to get out from under the mountain of possessions we have, and have all the best intentions of simplifying our lives … the truth is that we continue to have too much stuff.

Part of that is laziness, an attitude of “I’ll get to it later" … but the real driving force behind our too-much-stuffitis is fear.

Fear is what causes us to buy things we don’t really need. Fear keeps us holding onto stuff we don’t need.

Consider:

- You pack too much when you travel, and have a garage full of stuff, just in case you might need it. This is a fear that you might need something and not have it. It’s fear of lack of safety and certainty.

- You buy a lot of things for an upcoming event or trip because you don’t know what you might need. Your fear is that you’ll be unprepared. Again, it’s fear of lack of safety and certainty.

- You hold on to things you don’t use anymore because you might need it someday. You probably won’t, but you’re really not sure. Again, it’s fear of lack of safety and certainty.

- You keep books and other aspirational items (guitar you never learned, elliptical machine you don’t use) because you hope you’ll get to them someday, and letting go seems like a loss of hope. You fear not being the person you want to be. This is a fear of not being good enough as you are.

- You hold on to sentimental items, because you don’t want to lose the memories, or because it means a lot. Really, you’re afraid you will lose the love or relationship that these items represent (grandpa’s jacket represents your loving relationship with him). You fear the loss of love. This is a fear that the love you have now is not good enough.

- You don’t want to get rid of things because you paid a lot for them, and you fear that letting go would be a waste. Actually, if you’re not using them, it’s a waste to keep them. It’s hard to say what the fear is here … but you likely fear that if the original purchase was a mistake, things might not turn out well in the future. This is a fear that the present moment won’t turn out OK, or again, a fear of uncertainty.

- You keep a lot of clothes (or other similar items) because they’re a means of self-expression for you … and getting rid of many of those clothes would feel like you’re limiting your means of self-expression. You fear not having those options, not having the ability to be who you want to be. This is a fear that you’re not good enough as you are, without those items.

I could go on, but nearly all our possessions that aren’t absolute necessities (shelter, a bed, very minimal clothing, food, personal hygiene stuff, etc.) are bought and kept because of fears.

We want these items to comfort us, to help us cope with fears and anxieties, to help us feel prepared and more secure, to help us feel that we’ll be OK, to help us feel more certain about the future.

And of course, these items don’t actually do any of these things. We hope they will, but they never do. We never have more certainty about the future, and we continue to want more things to cope with fears that we’re not good enough, that things won’t turn out OK, and so on. The cycle doesn’t end.

So what’s the solution?

A Better Way to Cope With Fears

If we could find a different way of coping with these fears and anxieties, we wouldn’t need the stuff. We could pause before buying something out of fear, and decide not to buy it. We could finally get rid of much of the stuff we have lying around taking up space and mental energy. We could downsize, and live a more minimalist life.

So what’s another way to cope with these fears? Try this:

- First notice that you have fear. Notice that you’re being motivated out of fear. Notice that there’s some anxiety, some worry about uncertainty or insecurity, some desire for comfort.

- Stay with the fear. Our tendency is to run away from the fear, to try to seek comfort by buying something or eating comfort food or doing something relaxing. Running from the fear is what causes many of our problems. Stay, sit still, face the fear, breathe. Find the courage to go to the places we’re afraid of.

- Smile at the fear. Face this fear and smile at it. It is just a scared child inside you, nothing to run from, nothing to be upset about. It’s perfectly OK, perfectly natural, for fears to arise in us. Accept this fear in front of you, and smile at it. This smiling dissipates much of its power.

- Develop a friendliness with it. Be open and curious about your fear, see how it feels in your body, what is its quality? Investigate it with friendliness, get to know it like a new friend. Once you really learn what this fear feels like, really become unconditionally friendly with it, you begin to trust that you’ll be OK, that it will float away eventually like a cloud in the wide open expanse of the sky of your mind.

Friends with this fear, you can now decide how to act, unencumbered by the need to alleviate the fear with possessions. You can close the tab with your favorite online shopping site, you can put it on a 30-day list to look at later, when the urge has faded and the fear is no longer with you. You can let go of the possessions you do have, finally freeing yourself of this burden.

And in the end, you’ll find that you’re perfectly OK as you are, without needing to change, without needing anything to “express" who you are or improve you. And that’s worth more than all the possessions in the world.

The Minimalist Way to Declutter

If you’d like to go deeper into clearing clutter from your life, and mindfully clearing space for what’s important … join me in my Sea Change Program as I have created a new course: The Minimalist Way to Declutter.

It’ll be a great course, with two video lessons a week for next six weeks (into mid-August 2016). In addition, we’ll have a live video webinar, guest experts, and daily challenges.

We’ll talk about how to get clutter out of your life, how to figure out what’s important and how to make space for it, how to do a mindful declutter session every day, how to deal with clothes and sentimental items and digital clutter and your email inbox, and much more!

Join me here using a 7-day trial:

Posted: Friday, April 1, 2016

Previous post: Shannon’s Method: Overcome Habit Procrastination

About :: Uncopyright :: Archives :: Books :: Habit Program

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

A Technique for Producing Ideas

A Technique for Producing Ideas

In the foreword to James Webb Young’s book, A Technique for Producing Ideas, Keith Reinhard asks “How can a book first published in the 1940s be important to today’s creative people on the cutting edge?"

The answer lies in the question that inspired Webb’s book, “How do you get ideas?"

Webb argues that the production of ideas is a process, just like production of cars.

… the production of ideas, too, runs on an assembly line; that in this production the mind follows an operative technique which can be learned and controlled; and that its effective use is just as much a matter of practice in the technique as is the effective use of any tool.

The formula is simple but not easy.

First, the formula is so simple to state that few who hear it really believe in it.

Second, while simple to state, it actually requires the hardest kind of intellectual work to follow, so that not all who accept it use it.

That’s the same reason Warren Buffett has no problem sharing the secrets of investing in his shareholder letters (I recommend the real thing but if you’re pressed for time you could do worse than the Cliff Notes version.)

Training the mind requires that you learn principles and method.

In learning any art the important things to learn are, first, Principles, and second, Method. This is true of the art of producing ideas.

Particular bits of knowledge are nothing, because they are made up of what Dr. Robert Hutchins once called rapidly aging facts. Principles and method are everything.

[…]

So with the art of producing ideas. What is most valuable to know is not where to look for a particular idea, but how to train the mind in the method by which all ideas are produced and how to grasp the principles which are at the source of all ideas.

Echoing Einstein, Webb believed that the key to creativity could be found in new combinations of old things.

With regard to the general principles which underlie the production of ideas, it seems to me that there are two which are important.

The first of these has already been touched upon in the quotation from Pareto: namely, that an idea is nothing more or less than a new combination of old elements.

This is, perhaps the most important fact in connection with the production of ideas.

[…]

The second important principle involved is that the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships.

Here, I suspect, is where minds differ to the greatest degree when it comes to the production of ideas. To some minds each fact is a separate bit of knowledge. To others it is a link in a chain of knowledge. It has relationships and similarities. It is not so much a fact as it is an illustration of a general law applying to a whole series of facts.

[…]

Consequently the habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas.

Young expands on the notion that combinations, and thus relationships and connections between ideas, are the key.

An idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements [and] the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships. The habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas.

The process he advises involves 5 steps.

While we will all be familiar with each individual step, it is more important to recognize their relationship and “grasp the fact that the mind follows these five steps in definite order."

1. Gather Raw Material

Gathering raw material in a real way is not as simple as it sounds. It is such a terrible chore that we are constantly trying to dodge it. The time that ought to be spent in material gathering is spent in wool gathering. Instead of working systematically at the job of gathering raw material we sit around hoping for inspiration to strike us. When we do that we are trying to get the mind to take the fourth step in the idea-producing process while we dodge the preceding steps.

The materials which must be gathered are of two kinds: they are specific and they are general.

Part of this is what you set out to do when you create an idea and part of it is a life-long curiosity.

“Before passing on to the next step there are two practical suggestions I might make about this material-gathering process."

The first is that if you have any sizable job of specific material gathering to do it is useful to learn the card-index method of doing it.This is simply to get yourself a supply of those little 3 X 5 ruled white cards and use them to write down the items of specific information as you gather them. If you do this, one item to a card, after a while you can begin to classify them by sections of your subject. Eventually you will have a whole file box of them, neatly classified.

…

The second suggestion is that for storing up certain kinds of general material some method of doing it like a scrapbook or file is useful.

You will remember the famous scrapbooks which appear throughout the Sherlock Holmes stories, and how the master detective spent his time indexing and cross-indexing the old bits of material he gathered there.

2. The Mental Digestive Process

What you do is to take the different bits of material which you have gathered and feel them all over, as it were, with the tentacles of the mind. You take one fact, turn it this way and that, look at it in different lights, and feel for the meaning of it. You bring two facts together and see how they fit. What you are seeking now is the relationship, a synthesis where everything will come together in a neat combination, like a jig-saw puzzle.

3. Unconsciously Process

Drop the whole subject and put it out of your mind and let your subconscious do its thing.

It is important to realize that this is just as definite and just as necessary a stage in the process as the two preceding ones. What you have to do at this time, apparently, is to turn the problem over to your unconscious mind and let it work while you sleep.

4. A-Ha

Now, if you have really done your part in these three stages of the process you will almost surely experience the fourth.

Out of nowhere the Idea will appear.

It will come to you when you are least expecting it — while shaving, or bathing, or most often when you are half awake in the morning. It may waken you in the middle of the night.

5. The Final Stage

It requires a deal of patient working over to make most ideas fit the exact conditions, or the practical exigencies, under which they must work. And here is where many good ideas are lost. The idea man, like the inventor, is often not patient enough or practical enough to go through with this adapting part of the process. But it has to be done if you are to put ideas to work in a work-a-day world.

Do not make the mistake of holding your idea close to your chest at this stage. Submit it to the criticism of the judicious.

When you do, a surprising thing will happen. You will find that a good idea has, as it were, self-expanding qualities. It stimulates those who see it to add to it. Thus possibilities in it which you have overlooked will come to light.

Still curious? Read A Technique for Producing Ideas.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Seneca on Gathering Ideas And Combinatorial Creativity

Seneca on Gathering Ideas And Combinatorial Creativity

“Combinatory play," said Einstein, “seems to be the essential feature in productive thought."

Ruminating on the necessity of both reading and writing, so as not to confine ourselves to either, Seneca in one of his Epistles, advised that we engage in Combinatorial Creativity — that is, gather ideas, sift them, and combine them into a new creation.

We should follow, men say, the example of the bees, who flit about and cull the flowers that are suitable for producing honey, and then arrange and assort in their cells all that they have brought in; these bees, as our Vergil says,

Pack close the flowing honey,

And swell their cells with nectar sweet.It is not certain whether the juice which they obtain from the flowers forms at once into honey, or whether they change that which they have gathered into this delicious object by blending something therewith and by a certain property of their breath. For some authorities believe that bees do not possess the art of making honey, but only of gathering it … Certain others maintain that the materials which the bees have culled from the most delicate of blooming and flowering plants is transformed into this peculiar substance by a process of preserving and careful storing away, aided by what might be called fermentation,— whereby separate elements are united into one substance.

But I must not be led astray into another subject than that which we are discussing. We also, I say, ought to copy these bees, and sift whatever we have gathered from a varied course of reading, for such things are better preserved if they are kept separate; then, by applying the supervising care with which our nature has endowed us,— in other words, our natural gifts,— we should so blend those several flavors into one delicious compound that, even though it betrays its origin, yet it nevertheless is clearly a different thing from that whence it came.

Montaigne, perhaps echoing Seneca, reasoned that we must take knowledge and make it our own, Seneca comments:

We must digest it; otherwise it will merely enter the memory and not the reasoning power. Let us loyally welcome such foods and make them our own, so that something that is one may be formed out of many elements, just as one number is formed of several elements whenever, by our reckoning, lesser sums, each different from the others, are brought together. This is what our mind should do: it should hide away all the materials by which it has been aided, and bring to light only what it has made of them. Even if there shall appear in you a likeness to him who, by reason of your admiration, has left a deep impress upon you, I would have you resemble him as a child resembles his father, and not as a picture resembles its original; for a picture is a lifeless thing.

The Loeb Classic Library collection of Seneca’s Epistles in three volumes (1-65, 66-92, and 92-124), should be read by all in its entirety. Of course, if you don’t have time to read them all, you can read a heavily curated version of them.

(Image source)

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Building Blocks and Innovation

Building Blocks and Innovation

Most innovation comes from combining well-known, well-established, building blocks in new ways.

![]()

John Holland, a professor of two vastly different fields—psychology and engineering—at the University of Michigan, lectures frequently on innovative thinking.

According to Holland there are two steps to innovation. The first step is to try and find the right building blocks—the basic knowledge. Second, is the use of metaphors to relate understanding.

Holland is focused on innovation, but many readers of Farnam Street will recognize the first step—acquiring the building blocks—as the process for acquiring worldly wisdom.

Like us, Holland wants to connect well-known and well-established ideas from multiple disciplines in new ways to solve problems.

In our case, the basic building blocks are the big ideas in each major discipline. While this seems daunting, luckily, according to Charlie Munger “80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly wise person."

Domain Dependence and Linking

It’s important that you can link these models together and recognize them outside of the domain they are presented. Many people, for instance, don’t link the supply and demand from economics and equilibrium from physics. Yet in many ways they are the same thing. If you can’t recognize the forces at play outside of the system in which you learned about them, you are domain dependent.

In Antifragile, Nassim Taleb writes:

We are all, in a way, similarly handicapped, unable to recognize the same idea when it is presented in a different context. It is as if we are doomed to be deceived by the most superficial part of things, the packaging, the gift wrapping.

If you don’t have a basic understanding of each of the major models you won’t be able to link them together. And if you can’t link them together, you’re going to go through life like a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest.

Construction of a Model

According to Holland, “the construction of a mental model … closely resembles the construction of a metaphor:"

- There is a source system with an established aura of facts, interpretation and practice.

- There is a target system with a collection of observed phenomena that are difficult to interpret or explain.

- There is a translation from source to target that suggests a means of transferring inferences for the source into inferences for the target.

Seeing new connections requires models and metaphors. Holland continues:

For most who are heavily engaged in creative activities, be it in literature or the sciences, metaphor and model lie at the center of their activities. In the sciences, both the source and the target are best characterized as systems rather than isolated objects. … In the sciences, decisions about which properties of the source system are central for understanding the target, and which are incidental, are resolved by careful testing against the world. As a result of testing and deduction, a well-established model in the sciences accumulates a complicated aura of technique, interpretation, and consequences, much of it unwritten. One physicist will say to another “this is a conservation of mass problem" and immediately both will have in mind a whole array of knowledge associated with problems modeled in this way.

“The essence of metaphor," write Mark Johnson and George Lakoff in their book Metaphors We Live By, “is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another."

Holland posits that metaphors help us translate ideas into models, which form the building blocks of innovative thinking.

“In the same way that a metaphor helps communicate one concept by comparing it to another concept that is widely understood," Robert Hagstrom writes in Investing: The Last Liberal Art, “using a simple model to describe one idea can help us grasp the complexities of a similar idea. In both cases we are using one concept (the source) to better understand another (the target). Used this way, metaphors not only express existing ideas, they stimulate new ones."

Metaphor and Innovation

From the Credit Suisse Thought Leader Forum:

To understand the problems in any discipline, it is necessary to have deep knowledge in that discipline. To resolve those problems, it is often necessary to look at the problem through the filters of a different and often distant discipline. The simplest analogy to the phenomenon is simply perspective. It is very difficult to understand, say, the traffic patterns of a city if you are stuck in your car at rush hour. With the distance provided by a traffic helicopter, however, it is much easier to see the major thoroughfares, the bottlenecks and the overall dynamics of the traffic system. The shift in vantage point offers better understanding and new insights for your strategy. For more abstract challenges, the use of metaphor serves the same purpose as distance in the traffic example. If we are stuck on the challenge of distribution in a global manufacturing company, for example, it may be useful to apply models from other disciplines as metaphors. The model that we have developed and used for our distribution system has been quite effective over the years, but we just cannot seem to resolve some particular challenge. Perhaps we can learn something from other kinds of distribution systems. How does an ant colony collect and distribute its resources? How does the human body manage its circulation and processing of nutrients and wastes?

Three Keys to effectively applying metaphors

There are three keys to effectively applying metaphors to achieve insight and innovation. First, you must develop a deep understanding of the metaphorical system. You will gain no new insights if you look at the human circulatory system and say, “Aha! The brain tells the rest of the body where to send things!" If you draw conclusions too quickly, then more than likely you have only recreated your existing model of distribution systems – you are seeing the human body’s circulation system as if it were the distribution system of a global manufacturing firm. If you invest the time and effort to understand this complex new system on its own merits, then you might discover something interesting about your own discipline. For instance, the human circulatory system is one of several overlapping hierarchical systems that allow the human body to grow, heal, change and yet maintain homeostatic balance. How do those systems overlap? How are the priorities of those different systems balanced? What overlapping systems exist in our global manufacturing firm, and how do they interact? An in-depth study of a new complex system should force you to ask new questions about your own, seemingly familiar system.

The second key to applying metaphors is to recognize the value of the cognitive leap. As you map the models from one system onto another, the fit will never be perfect. Our global manufacturing firm is not a human body. Therefore the solution to our challenge will not lie in our suddenly believing this to be true. Instead, the solution will lie one or two steps away. As we look at the human circulatory system, we will encounter questions and tangential thoughts. “What performs the function of ‘hormones’ in our organization?" We will not, of course, implement a system of complex chemical exchanges in our organization, but this might lead us to think about our communication systems or decision-making metrics in a new way.

The final key is often the most frustrating for managers — only a very few of the ideas that this process produces will be highly valuable. Some of the ideas will be useless. Many of the ideas will be interesting but impractical or irrelevant. Other ideas will serve as useful, incremental improvements to your system. But only a rare few of these ideas will be truly revolutionary. The secret is the same in any game of statistics – you have to try large numbers of these metaphors for the big ideas to hit. These ideas are the outliers, not the norm, and while metaphor can push your thinking towards the innovative, no process can guarantee that your new ideas will be both different and effective. Many managers are willing to try this approach once or twice, and give up when it does not immediately return impressive results. … In order to discover great innovations, you must engage regularly in the search and recognize that most of your discoveries will have either marginal or moderate value. Creative combination is a process that increases your odds of discovering breakthrough innovations, but it cannot guarantee success. This is a tool, not a silver bullet.

While the audio quality leaves much to be desired, Holland gives an interesting TEDx talk introducing a lot of these ideas:

Filed Under: Domain Dependence, Innovation, John Holland, Language, Metaphor, Robert Hagstrom

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Steve Jobs on Creativity

Steve Jobs on Creativity

“Originality depends on new and striking combinations of ideas."

— Rosamund Harding

In a beautiful article for The Atlantic, Nancy Andreasen, a neuroscientist who has spent decades studying creativity, writes:

[C]reative people are better at recognizing relationships, making associations and connections, and seeing things in an original way—seeing things that others cannot see. … Having too many ideas can be dangerous. Part of what comes with seeing connections no one else sees is that not all of these connections actually exist.

The same point of view is offered by James Webb Young, who many years earlier, wrote:

An idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements [and] the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships.

A lot of creative luminaries think about creativity in the same way. Steve Jobs had a lot to say about creativity.

In I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words, editor George Beahm draws on more than 30 years of media coverage of Steve Jobs in order to find Jobs’ most thought-provoking insights on many aspects of life and creativity.

In one particularly notable excerpt Jobs says:

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

The more you learn about, the more you can connect things. This becomes an argument for a broad-based education. In his 2005 commencement address to the class of Stanford, Jobs makes the case for learning things that, at the time, may not offer the most practical benefit. Over time, however, these things add up to give you a broader base of knowledge from which to connect ideas:

Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn’t have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating.

None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me.

While education is important for building up a repository for which you can connect things, it’s not enough. You need broad life experiences as well.

I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words is full of things that will make you think.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Steve Jobs on Creativity

Steve Jobs on Creativity

“Originality depends on new and striking combinations of ideas."

— Rosamund Harding

In a beautiful article for The Atlantic, Nancy Andreasen, a neuroscientist who has spent decades studying creativity, writes:

[C]reative people are better at recognizing relationships, making associations and connections, and seeing things in an original way—seeing things that others cannot see. … Having too many ideas can be dangerous. Part of what comes with seeing connections no one else sees is that not all of these connections actually exist.

The same point of view is offered by James Webb Young, who many years earlier, wrote:

An idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements [and] the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships.

A lot of creative luminaries think about creativity in the same way. Steve Jobs had a lot to say about creativity.

In I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words, editor George Beahm draws on more than 30 years of media coverage of Steve Jobs in order to find Jobs’ most thought-provoking insights on many aspects of life and creativity.

In one particularly notable excerpt Jobs says:

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

The more you learn about, the more you can connect things. This becomes an argument for a broad-based education. In his 2005 commencement address to the class of Stanford, Jobs makes the case for learning things that, at the time, may not offer the most practical benefit. Over time, however, these things add up to give you a broader base of knowledge from which to connect ideas:

Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn’t have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating.

None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me.

While education is important for building up a repository for which you can connect things, it’s not enough. You need broad life experiences as well.

I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words is full of things that will make you think.

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

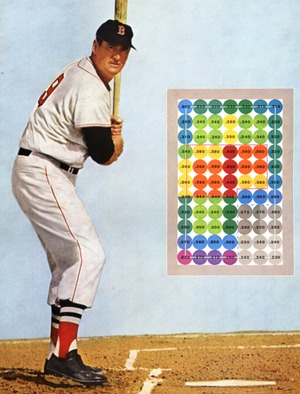

Ted Williams on how to make better decisions

What You Can Learn About Making Better Decisions From One of Baseball’s Greatest Hitters

Ted Williams was arguably the greatest pure hitter who ever played the game of baseball. He’s the last person to cross the magic .400 barrier. That’s exceptional. It also means he failed to get a hit 60% of the time.

How did he do it? And more importantly what can we learn from him that will help us make better decisions?

I’m not a huge baseball fan. I only read Williams book, The Science of Hitting, because Warren Buffett mentioned it in a comment on making better decisions.

I enjoyed the book much more than I thought I would.

Williams understood that an important aspect to improving the odds of making good choices is the ability to distinguish between decisions within our circle of competence and those on the outside.

The way we make decisions — our decision process — matters.

And Williams used a great process to tilt the odds in his favor.

You Need a Good Pitch

A good hitter can hit a pitch that is over the plate three times better than a great hitter with a questionable ball in a tough spot.

The first rule of hitting actually comes from a fellow baseball legend, Rogers Hornsby.

He told Williams that the single most important thing for a hitter was to get a good ball to hit.

Ever a student of the game, Williams carved the strike zone into 77 cells, each the size of a baseball.

Williams knew that swinging at balls in the best cells, the red ones, would allow him to bat pretty close to .400; deviating outside of that, and reaching for his worst spot, would reduce him to .230.

Patience would make the difference between a trip to the hall of fame and a ticket to the minors.

Our Strikezone

We all have a strike zone, this is our circle of competence. This is an area in which we are capable of understanding with a high degree of probability the relevant variables and likely outcome.

Making decisions within our circle improves the odds we’ll do well. This is our sweet spot and it’s different for all of us.

The problem is everyone wants to have a large circle. We think bigger is better. But the size of the circle is not really what’s most important.

Knowing the boundaries of our circle of competence is more important than its size. Familiarity with something is different than competence.

Charlie Munger says “It’s not a competency if you don’t know the edge of it."

And Warren Buffett, elaborating on the same topic, wrote:

“If we have a strength, it is in recognizing when we are well within our cycle of competence and when we are approaching the perimeter. Predicting the long term economics of companies that operate in fast-changing industries is simply far beyond our perimeter. If others claim predictive skills in those industries—and seem to have claims validated by the behaviour of the stock market we neither envy not emulate them. Instead,w e just stick with what we understand. If we stray, we will have done so inadvertently, not because we got restless and substituted hope for rationality."

Unlike Williams, Buffett can’t be called out on strikes if he resists pitches that are barely in the strike zone. He can, quite literally, wait for the perfect pitch. That explains why he bats pretty close to 1.0 while Williams had to settle for less.

In some decisions, such as investing, we can choose to do the same thing. We can sit around, read, and wait for the right opportunity. Most decisions, however, are not of that nature.

We simply don’t have the option to wait for the perfect pitch. We have to make decisions in an uncertain world with imperfect information.

Knowing the boundary of our aptitude, where we bat above average and where we don’t, can help guide those decisions and how we make them.

Making decisions outside of our circle of competence (i.e., we don’t know what we’re doing) is riskier than making decisions inside our circle (i.e., where we do know what we’re doing.)

Williams batting average dropped off when he swung outside his core, and so to will ours.

If we have to decide something and we know we’re not in our sweet spot, we can take steps to improve the odds of making the a better decision. Or, at the very least, acknowledge that the decision we’re making is risky; We know we’re the patsy.

Whatever decision you’re making, know where it falls in your strike zone. To the extent possible you should attempt to deal with things that you are capable of understanding.

(Editor’s Note: This is an updated article that I wrote and originally posted on The Reformed Broker.)

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016

Decisions Under Uncertainty

Decisions Under Uncertainty

If you’re a knowledge worker you make decisions everyday. In fact, whether you realize it or not, decisions are your job.

Decisions are how you make a living. Of course not every decision is easy. Decisions tend to fall into different categories. The way we approach the actual decision should vary based on category.

Here are a few basic categories that decisions fall into.

There are decisions where:

- Outcomes are known. In this case the range of outcomes is known and the individual outcome is also known. This is the easiest way to make decisions. If I hold out my hand and drop a ball, it will fall to the ground. I know this with near certainly.

- Outcomes are unknown, but probabilities are known.In this case the range of outcomes are known but the individual outcome is unknown. This is risk. Think of this as going to Vegas and gambling. Before you set foot at the table, all of the outcomes are known as are the probabilities of each. No outcome surprises an objective third party.

- Outcomes are unknown and probabilities are unknown. In this case the distribution of outcomes are unknown and the individual outcomes are necessarily unknown. This is uncertainty.

We often think we’re making decisions in #2 but we’re really operating in #3. The difference may seem trivial but it makes a world of difference.

Decisions Under Uncertainty

Ignorance is a state of the world where some possible outcomes are unknown: when we’ve moved from #2 to #3.

One way to realize how ignorant we are is to look back, read some old newspapers, and see how often the world did something that wasn’t even imagined.

Some examples include the Arab Spring, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the financial meltdown.

We’re prepared for a world much like #2 — the world of risk, with known outcomes and probability that can be estimated, yet we live in a world with a closer resemblance to #3.

Read part two of this series: Two types of ignorance.

References: Ignorance: Lessons from the Laboratory of Literature (Joy and Zeckhauser).

Filed Under: Culture, Decision Making, Richard Zeckhauser, Risk, Uncertainty

Brandon M. Dolin Posted on October 14th, 2016