The Power of ‘Why?’ and ‘What If?’

The Power of ‘Why?’ and ‘What If?’

mobile.nytimes.com | July 2, 2016Recently I had a conversation with a chief executive who expressed concern about several of her senior managers. They were smart, experienced, competent. So what was the problem? “They’re not asking enough questions,” she said.

This wouldn’t have been a bad thing in the business world of a few years ago, where the rules for success were: Know your job, do your work, and if a problem arises, solve it and don’t bother us with a lot of questions.

But increasingly I’m finding that business leaders want the people working around them to be more curious, more cognizant of what they don’t know, and more inquisitive — about everything, including “Why am I doing my job the way I do it?” and “How might our company find new opportunities?”

I may be hyper-aware of this trend because I think of myself as a “questionologist,” having studied the art of questioning and written a book about it. But I also think there are real forces in business today that are causing people to value curiosity and inquiry more than in the past.

Companies in many industries today must contend with rapid change and rising uncertainty. In such conditions, even a well-established company cannot rest on its expertise; there is pressure to keep learning what’s new and anticipating what’s next. It’s hard to do any of that without asking questions.

Steve Quatrano, a member of the Right Question Institute, a nonprofit research group, explains that the act of formulating questions enables us “to organize our thinking around what we don’t know.” This makes questioning a good skill to hone in dynamic times.

Asking questions can help spark the innovative ideas that many companies hunger for these days. In the research for my book, I studied business breakthroughs — including the invention of the Polaroid instant camera and the Nest thermostat and the genesis of start-ups like Netflix, Square and Airbnb — and found that in each case, some curious soul looked at a current problem and asked insightful questions about why that problem existed and how it might be tackled.

The Polaroid story is my favorite: The inspiration for the instant camera sprang from a question asked in the mid-1940s by the 3-year-old daughter of its inventor, Edwin H. Land. She was impatient to see a photo her father had just snapped, and when he tried to explain that the film had to be processed first, she wondered aloud, “Why do we have to wait for the picture?”

One might assume that people can easily ask such questions, given that children do it so well. But research shows that question-asking peaks at age 4 or 5 and then steadily drops off, as children pass through school (where answers are often more valued than questions) and mature into adults. By the time we’re in the workplace, many of us have gotten out of the habit of asking fundamental questions about what’s going on around us. And some people worry that asking questions at work reveals ignorance or may be seen as slowing things down.

So how can companies encourage people to ask more questions? There are simple ways to train people to become more comfortable and proficient at it. For example, question formulation exercises can be used as a substitute for conventional brainstorming sessions. The idea is to put a problem or challenge in front of a group of people and instead of asking for ideas, instruct participants to generate as many relevant questions as they can. Kristi Schaffner, an executive at Microsoft, regularly conducts such exercises there and says they sharpen analytical skills.

Getting employees to ask more questions is the easy part; getting management to respond well to those questions can be harder. When leaders claim they want “everyone to ask more questions,” I sometimes (in my bolder moments) ask: “Do you really want that? And what will you do with those questions once people start asking them?”

For questioning to thrive in a company, management must find ways to reward the behavior — if only by acknowledging the good questions that have been asked. For example, I visited one company that asked all employees to think of “what if” and “how might we” questions about the company’s goals and plans. Management and employees together decided which of these mission questions were best, then displayed them on banners on the walls.

Leaders can also encourage companywide questioning by being more curious and inquisitive themselves. This is not necessarily easy for senior executives, who are used to being the ones with the answers. I’ve noticed during questioning exercises at some companies that top executives sit in the back of the room, laptops open, attending to other business; they seem to think their employees are the only ones who need to learn. As they do this, these leaders are modeling precisely the kind of incurious behavior they’re trying to change in others.

They could set a better example by asking “why” and “what if” — while asking others to do likewise. And as the questions proliferate, some good answers are likely to follow.

© 2016 The New York Times Company.The content you have chosen to save (which may include videos, articles, images and other copyrighted materials) is intended for your personal, noncommercial use. Such content is owned or controlled by The New York Times Company or the party credited as the content provider. Please refer to nytimes.com and the Terms of Service available on its website for information and restrictions related to the content. Recommend this article on Pocket!

Recommend

Original Page: http://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/07/03/jobs/the-power-of-why-and-what-if.html

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

Think Less, Think Better

Photo by: Gérard DuBois

A FRIEND of mine has a bad habit of narrating his experiences as they are taking place. I tease him for being a bystander in his own life. To be fair, we all fail to experience life to the fullest. Typically, our minds are too occupied with thoughts to allow complete immersion even in what is right in front of us.

Sometimes, this is O.K. I am happy not to remember passing a long stretch of my daily commute because my mind has wandered and my morning drive can be done on autopilot. But I do not want to disappear from too much of life. Too often we eat meals without tasting them, look at something beautiful without seeing it. An entire exchange with my daughter (please forgive me) can take place without my being there at all.

Recently, I discovered how much we overlook, not just about the world, but also about the full potential of our inner life, when our mind is cluttered. In a study published in this month’s Psychological Science, the graduate student Shira Baror and I demonstrate that the capacity for original and creative thinking is markedly stymied by stray thoughts, obsessive ruminations and other forms of “mental load." Many psychologists assume that the mind, left to its own devices, is inclined to follow a well-worn path of familiar associations. But our findings suggest that innovative thinking, not routine ideation, is our default cognitive mode when our minds are clear.

In a series of experiments, we gave participants a free-association task while simultaneously taxing their mental capacity to different degrees. In one experiment, for example, we asked half the participants to keep in mind a string of seven digits, and the other half to remember just two digits. While the participants maintained these strings in working memory, they were given a word (e.g., shoe) and asked to respond as quickly as possible with the first word that came to mind (e.g., sock).

We found that a high mental load consistently diminished the originality and creativity of the response: Participants with seven digits to recall resorted to the most statistically common responses (e.g., white/black), whereas participants with two digits gave less typical, more varied pairings (e.g., white/cloud).

In another experiment, we found that longer response times were correlated with less diverse responses, ruling out the possibility that participants with low mental loads simply took more time to generate an interesting response. Rather, it seems that with a high mental load, you need more time to generate even a conventional thought. These experiments suggest that the mind’s natural tendency is to explore and to favor novelty, but when occupied it looks for the most familiar and inevitably least interesting solution.

In general, there is a tension in our brains between exploration and exploitation. When we are exploratory, we attend to things with a wide scope, curious and desiring to learn. Other times, we rely on, or “exploit," what we already know, leaning on our expectations, trusting the comfort of a predictable environment. We tend to be more exploratory when traveling to a new country, whereas we are more inclined toward exploitation when returning home after a hard day at work.

Much of our lives are spent somewhere between those extremes. There are functional benefits to both modes: If we were not exploratory, we would never have ventured out of the caves; if we did not exploit the certainty of the familiar, we would have taken too many risks and gone extinct. But there needs to be a healthy balance. Our study suggests that your internal exploration is too often diminished by an overly occupied mind, much as is the case with your experience of your external environment.

In everyday life, you may find yourself “loading" your mind in various ways: memorizing a list of groceries to buy later at the supermarket, rehearsing the name of someone you just met so you don’t forget it, practicing your pitch before entering an important meeting. There are also, of course, the ever-present wanderings of a normal mind. And there are more pathological, or at least more chronic, sources of mental load, such as the ruminative thought patterns characteristic of stress, anxiety and depression. All these loads can consume mental capacity, leading to dull thought and anhedonia — a flattened ability to experience pleasure.

My birthday gift to myself for the last couple of years has been a week of silence at a vipassana meditation retreat. Being silent for a week, and trying to empty your mind of thought, is not for the faint of heart, but I do wish that everyone could try it at least once. During my first retreat, I wondered how a simple tomato could taste so good, why I did not mind physical discomfort as much, how looking at a single flower for 45 minutes was even possible, let alone so gratifying. My thoughts — when I returned to the act of thinking about something rather than nothing — were fresher and more surprising.

It is clear to me that this ancient meditative practice helps free the mind to have richer experiences of the present. Except when you are flying an F-16 aircraft or experiencing extreme fear or having an orgasm, your life leaves too much room for your mind to wander. As a result, only a small fraction of your mental capacity remains engaged in what is before it, and mind-wandering and ruminations become a tax on the quality of your life. Honing an ability to unburden the load on your mind, be it through meditation or some other practice, can bring with it a wonderfully magnified experience of the world — and, as our study suggests, of your own mind.

© 2016 The New York Times Company.

The content you have chosen to save (which may include videos, articles, images and other copyrighted materials) is intended for your personal, noncommercial use. Such content is owned or controlled by The New York Times Company or the party credited as the content provider. Please refer to nytimes.com and the Terms of Service available on its website for information and restrictions related to the content.

Enjoy this article? Recommend it to your followers!

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

An Introduction to the Kantian Fairness Tendency

farnamstreetblog.com

Farnam Street helps you make better decisions, innovate, and avoid stupidity.

With over 350,000 monthly readers and more than 88,000 subscribers to our popular weekly digest, we've become an online intellectual hub.

The Kantian Fairness Tendency refers to the pursuit of perfect fairness which causes a lot of terrible problems.

Charlie Munger, twice referenced this mental model. First in this UCCB talk:

It is not always recognized that, to function best, morality should sometimes appear unfair, like most worldly outcomes. The craving for perfect fairness causes a lot of terrible problems in system function. Some systems should be made deliberately unfair to individuals because they’ll be fairer on average for all of us. I frequently cite the example of having your career over, in the Navy, if your ship goes aground, even if it wasn’t your fault. I say the lack of justice for the one guy that wasn’t at fault is way more than made up by a greater justice for everybody when every captain of a ship always sweats blood to make sure the ship doesn’t go aground. Tolerating a little unfairness to some to get a greater fairness for all is a model I recommend to all of you. But again, I wouldn’t put it in your assigned college work if you want to be graded well, particularly in a modern law school wherein there is usually an over-love of fairness-seeking process.

And second in his essay entitled: The Psychology of Human Misjudgment:

Kant was famous for his “categorical imperative," a sort of a “golden rule" that required humans to follow those behavior patterns that, if followed by all others, would make the surrounding human system work best for everybody. And it is not too much to say that modern acculturated man displays, and expects from others, a lot of fairness as thus defined by Kant.

In a small community having a one-way bridge or tunnel for autos, it is the norm in the United States to see a lot of reciprocal courtesy, despite the absence of signs or signals. And many freeway drivers, including myself, will often let other drivers come in front of them, in lane changes or the like, because that is the courtesy they desire when roles are reversed. Moreover, there is, in modern human culture, a lot of courteous lining up by strangers so that all are served on a “firstcome-first-served" basis.

Also, strangers often voluntarily share equally in unexpected, unearned good and bad fortune. And, as an obverse consequence of such “fair-sharing" conduct, much reactive hostility occurs when fairsharing is expected yet not provided. It is interesting how the world’s slavery was pretty well abolished during the last three centuries after being tolerated for a great many previous centuries during which it coexisted with the world’s major religions. My guess is that Kantian Fairness Tendency was a major contributor to this result.

* * *

Professor Sanjay Bakshi makes a connection between the Kantian Fairness Tendency and the “law of the higher good" from Machiavelli’s The Prince. He had this to say to his students:

Machiavelli’s “The Prince" is a great book and should be made compulsory reading for all MBA students.

To many people, The Prince is an evil book. But Joseph L. Badaracco, who teaches a hugely popular course titled “The Moral Leader" at the Harvard Business School uses this book to teach ethics. And he teaches ethics by telling students to follow Machiavelli’s advice in The Prince.

In an interview, Badaracco has said that four different takes on The Prince usually emerge in classroom discussions of The Prince at HBS:

Version 1 : “This book is a mess. It was written by a guy who hoped to get to the center of things, was there briefly, offended some of the wrong Medicis, was exiled, was tortured, and wanted to get back in." It’s “a scholar’s dream because you can find anything you want in it and play intellectual games. But just put it aside."

Version 2 : “Now wait a minute. There’s some good common sense in there. Machiavelli is basically saying that if you want to make an omelet you have to break some eggs… To do some right things, you may have to not do some other right things."

Version 3 : Other students believe the book is still around because it’s so evil. Why is it evil? “If you look closely at The Prince," he said, “it’s quite interesting what isn’t in the book. Nothing about religion. Nothing about the Church. Nothing about God. There’s nothing about spirituality. Almost nothing about the law. Almost nothing about traditions. You’re out there on your own doing what works for you in terms of naked ambition."

Version 4 : “A fourth Prince that other students uncover is the most interesting one, in Badaracco’s mind. Students find that the book reveals a kind of worldview, he says, and it’s not an evil worldview. This version goes: “If you’re going to make progress in the world you’ve got to have a clear sense, a realistic sense, an unsentimental sense, of how things really work: the mixed motives that compel some people and the high motives that compel some others. And the low motives that unfortunately captivate other people." Students who claim the fourth Prince, Badaracco said, believe that if they’re going to make a difference, it’s got to be in this world, “and not in some ideal world that you would really like to live in."

One of my favourite mental models comes from The Prince. I call this model, the “law of the higher good“. Before I read The Prince, I read an excellent book called, “The Contrarian Guide to Leadership" by Steven Sample. In this book, which was recommended by Mr. Munger, Sample’s thoughts on the law of the higher good from The Prince resonated very well with what Mr. Munger has been advocating for years.

I reproduce here an extract from Sample’s book which deals with the law of the higher good:

“Let me clarify the most fundamental misunderstanding. Machiavelli was not an immoral or even an amoral man; as mentioned earlier, he had a strong set of moral principles. But he was driven by the notion of a higher good: an orderly state in which citizens can move about at will, conduct business, safeguard their families and possessions, and be free of foreign intervention or domination. Anything which could harm this higher good, Machiavelli argued, must be opposed vigorously and ruthlessly. Failure to do so out of either weakness or kindness was condemned by Machiavelli as being contrary to the interests of the state, just as it would be contrary to the interests of a patient for his surgeon to refuse to perform a needed operation out of fear that doing so would inflict pain on the patient."

The law of the higher good is a terribly useful model for leaders because it forces them to think about things from a totally different perspective.

Here’s a hypothetical situation to ponder about:

You are in charge of running a retail store and one of your cashiers, an elderly woman, is caught committing a minor embezzlement. Fearing that she might be dismissed, she approaches you to plead forgiveness. She tells you that this is the first time she embezzled money from the company and promises that she’ll never do it again. She tells you about her sad situation, namely that her husband is very ill and that she was going to use the money to buy medicines for him. She becomes extremely emotional and your heart is melting. What do you do?

Something similar to the above situation was described by Mr. Munger in a talk given by him. He used two models to produce his answer. The first model was probability. Mr. Munger implores you to reduce the problem to the mathematics of Fermat/Pascal by asking the question: How likely is it that the old woman’s statement, “I’ve never done it before, I’ll never do it again" is true?

Note that this question has nothing whatsoever to do with the circumstances in this particular instance of embezzlement. Rather, Munger is relying on his knowledge of the theory of probability. He asks: “If you found 10 embezzlements in a year, how many of them are likely to be first offences?"

The possible actions are: (1) She is lying and you fire her (good outcome – because it cures the problem and sends the right signals); (2) She is telling the truth and you fire her (bad outcome for her but good outcome for system integrity); (3) She is lying and you pardon her (bad outcome for system integrity); and (4) She is telling the truth and you pardon her (bad outcome for system integrity because it will send the wrong signal that its ok to embezzle once).

Weighed with probabilities, and after considering signalling effects of your actions on other people’s incentives and its effect on system integrity, its clear that the woman should be fired.

Looked this way, this is not a legal problem or an ethical problem. Its an arithmetical problem with a simple solution. This extreme reductionism of practical problems to a fundamental discipline (in this case mathematics), is, of course, the hallmark of the Munger way of thinking and living.

So, from a leader’s perspective, it’s more important to have the right systems with the right incentives in place, rather than trying to be fair to one person – even if that person is the leader or someone close to the leader.

The logic is that leaders must look at such situations from their civilization’s point of view rather than the viewpoint of an individual. If we create systems which encourage embezzlements, or tolerate such systems, we’ll ruin our civilization. If we don’t punish the woman, the idea that its ok to do minor embezzlement once in a while, will spread because of incentive effects, and social proof (everyone’s doing it so its ok). And we cannot let that idea spread because that will ruin our civilization. Its that simple.

Kantian Fairness is part of the Farnam Street latticework of Mental Models.

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

Bias from Disliking/Hating

(This is a follow-up to our post on the Bias from Liking/Loving, which you can find here.)

Think of a cat snarling and spitting, lashing with its tail and standing with its back curved. Her pulse is elevated, blood vessels constricted and muscles tense. This reaction may sound familiar, because everyone has experienced the same tensed-up feeling of rage at least once in their lives.

When rage is directed towards an external object, it becomes hate. Just as we learn to love certain things or people, we learn to hate others.

There are several cognitive processes that awaken the hate within us and most of them stem from our need for self-protection.

Reciprocation

We tend to dislike people who dislike us (and, true to Newton, with equal strength.) The more we perceive they hate us, the more we hate them.

Competition

A lot of hate comes from scarcity and competition. Whenever we compete for resources, our own mistakes can mean good fortune for others. In these cases, we affirm our own standing and preserve our self-esteem by blaming others.

Robert Cialdini explains that because of the competitive environment in American classrooms, school desegregation may increase the tension between children of different races instead of decreasing it. Imagine being a secondary school child:

If you knew the right answer and the teacher called on someone else, you probably hoped that he or she would make a mistake so that you would have a chance to display your knowledge. If you were called on and failed, or if you didn’t even raise your hand to compete, you probably envied and resented your classmates who knew the answer.

At first we are merely annoyed. But then as the situation fails to improve and our frustration grows, we are slowly drawn into false attributions and hate. We keep blaming and associating “the others" who are doing better with the loss and scarcity we are experiencing (or perceive we are experiencing). That is one way our emotional frustration boils into hate.

Us vs. Them

The ability to separate friends from enemies has been critical for our safety and survival. Because mistaking the two can be deadly, our mental processes have evolved to quickly spot potential threats and react accordingly. We are constantly feeding information about others into our “people information lexicon" that forms not only our view of individuals, whom we must decide how to act around, but entire classes of people, as we average out that information.

To shortcut our reactions, we classify narrowly and think in dichotomies: right or wrong, good or bad, heroes or villains. (The type of Grey Thinking we espouse is almost certainly unnatural, but, then again, so is a good golf swing.) Since most of us are merely average at everything we do, even superficial and small differences, such as race or religious affiliation, can become an important source of identification. We are, after all, creatures who seek to belong to groups above all else.

Seeing ourselves as part of a special, different and, in its own way, superior group, decreases our willingness to empathize with the other side. This works both ways – the hostility towards the others also increases the solidarity of the group. In extreme cases, we are so drawn towards the inside view that we create a strong picture of the enemy that has little to do with reality or our initial perceptions.

From Compassion to Hate

We think of ourselves as compassionate, empathetic and cooperative. So why do we learn to hate?

Part of the answer lies in the fact that we think of ourselves in a specific way. If we cannot reach a consensus, then the other side, which is in some way different from us, must necessarily be uncooperative for our assumptions about our own qualities to hold true.

Our inability to examine the situation from all sides and shake our beliefs, together with self-justifying behavior, can lead us to conclude that others are the problem. Such asymmetric views, amplified by strong perceived differences, often fuel hate.

What started off as odd or difficult to understand, has quickly turned into unholy.

If the situation is characterized by competition, we may also see ourselves as a victim. The others, who abuse our rights, take away our privileges or restrict our freedom are seen as bullies who deserve to be punished. We convince ourselves that we are doing good by doing harm to those who threaten to cross the line.

This is understandable. In critical times our survival indeed may depend on our ability to quickly spot and neutralize dangers. The cost of a false positive – mistaking a friend for a foe – is much lower than the potentially fatal false negative of mistaking our adversaries for innocent allies. As a result, it is safest to assume that anything we are not familiar with is dangerous by default. Natural selection, by its nature, “keeps what works," and this tendency towards distrust of the unfamiliar probably survived in that way.

The Displays of Hate

Physical and psychological pain is very mobilizing. We despise foods that make us nauseous and people that have hurt us. Because we are scared to suffer, we end up either avoiding or destroying the “enemy", which is why revenge can be pursued with such vengeance. In short, hate is a defense against enduring pain repeatedly.

There are several ways that the bias for disliking and hating display themselves to the outer world. The most obvious of them is war, which seems to have been more or less prevalent throughout the history of mankind.

This would lead us to think that war may well be unavoidable. Charlie Munger offers the more moderate opinion that while hatred and dislike cannot be avoided, the instances of war can be minimized by channeling our hate and fear into less destructive behaviors. (A good political system allows for dissent and disagreement without explosions of blood upheaval.)

Even with the spread of religion, and the advent of advanced civilization, modern war remains pretty savage. But we also get what we observe in present-day Switzerland and the United States, wherein the clever political arrangements of man “channel" the hatreds and dislikings of individuals and groups into nonlethal patterns including elections.

But these dislikings and hatreds that are arguably inherent to our nature never go away completely and transcend themselves into politics. Think of the dichotomies. There is the left versus the right wing, the nationalists versus the communists and libertarians vs. authoritarians. This might be the reason why there are maxims like: “Politics is the art of marshaling hatreds."

Finally, as we move away from politics, arguably the most sophisticated and civilized way of channeling hatred is litigation. Charlie Munger attributes the following words to Warren Buffett:

“A major difference between rich and poor people is that the rich people can spend their lives suing their relatives."

While most of us reflect on our memories of growing up with our siblings with fondness, there are cases where the competition for shared attention or resources breeds hatred. If the siblings can afford it, they will sometimes litigate endlessly to lay claims over their parents’ property or attention.

Under the Influence of Bias

There are several ways that bias from hating can interfere with our normal judgement and lead to suboptimal decisions.

“Hating can interfere with our normal judgement and lead to suboptimal decisions." Click To Tweet

Ignoring Virtues of The Other Side

Michael Faraday was once asked after a lecture whether he implied that a hated academic rival was always wrong. His reply was short and firm “He’s not that consistent." Faraday must have recognized the bias from hating and corrected for it with the witty comment.

What we should recognize here is that no situation is ever black or white. We all have our virtues and we all have our weaknesses. However, when possessed by the strong emotions of hate, our perceptions can be distorted to the extent that we fail to recognize any good in the opponent at all. This is driven by consistency bias, which motivates us to form a coherent (“she is all-round bad") opinion of ourselves and others.

Association Fueled Hate

The principle of association goes that the nature of the news tends to infect the teller. This means that the worse the experience, the worse the impression of anything related to it.

Association is why we blame the messenger who tells us something that we don’t want to hear even when they didn’t cause the bad news. (Of course, this creates an incentive not to speak truth and avoid giving bad news.)

A classic example is the unfortunate and confused weatherman, who receives hate mail, whenever it rains. One went so far as to seek advice from the Arizona State professor of psychology, Robert Cialdini, whose work we have discussed before.

Cialdini explained to him that in light of the destinies of other messengers, he was born lucky. Rain might ruin someone’s holiday plans, but it will rarely change the destiny of a nation, which was the case of Persian war messengers. Delivering good news meant a feast, whereas delivering bad news resulted in their death.

The weatherman left Cialdini’s office with a sense of privilege and relief.

“Doc," he said on his way out, “I feel a lot better about my job now. I mean, I’m in Phoenix where the sun shines 300 days a year, right? Thank God I don’t do the weather in Buffalo."

Fact Distortion

Under the influence of liking or disliking bias we tend to fill gaps in our knowledge by building our conclusions on assumptions, which are based on very little evidence.

Imagine you meet a woman at a party and find her to be a self-centered, unpleasant conversation partner. Now her name comes up as someone who could be asked to contribute to a charity. How likely do you feel it is that she will give to the charity?

In reality, you have no useful knowledge, because there is little to nothing that should make you believe that people who are self-centered are not also generous contributors to charity. The two are unrelated, yet because of the well-known fundamental attribution error, we often assume one is correlated to the other.

By association, you are likely to believe that this woman is not likely to be generous towards charities despite lack of any evidence. And because now you also believe she is stingy and ungenerous, you probably dislike her even more.

This is just an innocent example, but the larger effects of such distortions can be so extreme that they lead to a major miscognition. Each side literally believes that every single bad attribute or crime is attributable to the opponent.

Charlie Munger explains this with a relatively recent example:

When the World Trade Center was destroyed, many Pakistanis immediately concluded that the Hindus did it, while many Muslims concluded that the Jews did it. Such factual distortions often make mediation between opponents locked in hatred either difficult or impossible. Mediations between Israelis and Palestinians are difficult because facts in one side’s history overlap very little with facts from the other side’s. These distortions and the overarching mistrust might be why some conflicts seem to never end.

Avoiding Being Hated

To varying degrees we value acceptance and affirmation from others. Very few of us wake up wanting to be disliked or rejected. Social approval, at its heart the cause of social influence, shapes behavior and contributes to conformity. Francois VI, Duc de La Rochefoucauld wrote: “We only confess our little faults to persuade people that we have no big ones."

Remember the old adage, “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down." This is why we don’t openly speak the truth or question people, we don’t want to be the nail.

How do we resolve hate?

It is only normal that we can find more common ground with some people than with others. But are we really destined to fall into the traps of hate or is there a way to take hold of these biases?

That’s a question worth over a hundred million lives. There are ways that psychologists think that we can minimize prejudice against others.

Firstly, we can engage with others in sustained close contact to breed our familiarity. The contact must not only be prolonged, but also positive and cooperative in nature – either working towards a common cause or against a common enemy.

Secondly, we also reduce prejudice by attaining equal status in all aspects, including education, income and legal rights. This effect is further reinforced, when equality is supported not only “on paper", but also ingrained within broader social norms.

And finally the obvious – we should practice awareness of our own emotions and ability to hold back on the temptations to dismiss others. Whenever confronted with strong feelings it might simply be best to sit back, breathe and do our best to eliminate the distorted thinking.

***

Bias from Disliking/Hating Click To Tweet

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

Mental Model: Bias from Liking/Loving

farnamstreetblog.com

Mental Model: Bias from Liking/Loving

The decisions that we make are rarely impartial. Most of us already know that we prefer to take advice from people that we like. We also tend to more easily agree with opinions formed by people we like. This tendency to judge in favor of people and symbols we like is called the bias from liking or loving.

We are more likely to ignore faults and comply with wishes of our friends or lovers rather than random strangers. We favor people, products, and actions associated with our favorite celebrities. Sometimes we even distort facts to facilitate love. The influence that our friends, parents, lovers and idols exert on us can be enormous.

In general, this is a good thing, a bias that adds on balance rather than subtracts. It helps us form successful relationships, it helps us fall in love (and stay in love), it helps us form attachments with others that give us great happiness.

But we do want to be aware of where this tendency leads us awry.

For example, some people and companies have learnt to use this influence to their advantage.

In his bestseller on social psychology Influence, Robert Cialdini tells a story about the successful strategy of Tupperware, which at the time reported sales of over $2.5 million a day. As many of us know, the company for a long time sold its kitchenware at parties thrown by friends of the potential customers. At each party there was a Tupperware representative taking orders, but the hostess, the friend of the invitees, received a commission.

These potential customers are not blind to the incentives and social pressures involved. Some of them don’t mind it, others do, but all admit a certain degree of helplessness in their situation. Cialdini recalls a conversation with one of the frustrated guests:

It’s gotten to the point now where I hate to be invited to Tupperware parties. I’ve got all the containers I need; and if I wanted any more, I could buy another brand cheaper in the store. But when a friend calls up, I feel like I have to go. And when I get there, I feel like I have to buy something. What can I do? It’s for one of my friends.

We are more likely to buy in a familiar, friendly setting and under the obligation of friendship rather than from an unfamiliar store or a catalogue. We simply find it much harder to say “no" or disagree when it’s a friend. The possibility of ruining the friendship, or seeing our image altered in the eyes of someone we like, is a powerful motivator to comply.

The Tupperware example is a true “lollapalooza" in favor of manipulating people into buying things. Besides the liking tendency, there are several other factors at play: commitment/consistency bias, a bias from stress, an influence from authority, a reciprocation effect, and some direct incentives and disincentives, at least! (Lollapaloozas, something we’ll talk more about in the future, are when several powerful forces combine to create a non-linear outcome. A good way to think of this conceptually for now is that 1+1=3.)

***

The liking tendency is so strong that it stretches beyond close friendships. It turns out we are also more likely to act in favor of certain types of strangers. Can you recall meeting someone with whom you hit it off instantly, where it almost seemed like you’d known them for years after a 20-minute conversation? Developing such an instant bond with a stranger may seem like a mythical process, but it rarely is. There are several tactics that can be used to make us like something, or someone, more than we otherwise would.

Appearance and the Halo Effect

We all like engaging in activities with beautiful people. This is part of an automatic bias that falls into a category called The Halo Effect.

The Halo Effect occurs when a specific, positive characteristic determines the way a person is viewed by others on other, unrelated traits. In the case of beauty, it’s been shown that we automatically assign favorable yet unrelated traits such as talent, kindness, honesty, and intelligence, with those we find physically attractive.

For the most part, this attribution happens unnoticed. For example, attractive candidates received more than twice as many votes as unattractive candidates in the 1974 Canadian federal elections. Despite the ample evidence of predisposition towards handsome politicians, follow-up research demonstrated that nearly three-quarters of Canadians surveyed strongly denied the influence of physical appearance in their voting decisions.

The power of the Halo Effect is that it’s mostly happening beneath the level of consciousness.

“The power of the Halo Effect is that it's mostly happening beneath the level of consciousness." Click To Tweet

Similar forces are at play when it comes to hiring decisions and pay. While employers deny that they are strongly influenced by looks, studies show otherwise.

In one study evaluating hiring decisions based on simulated interviews, the applicants’ grooming played a greater role in the outcome than job qualifications. Partly, this has a rational basis. We might assume that someone who shows up without the proper “look" for the job may be deficient in other areas. If they couldn’t shave and put a tie on, how are we to expect them to perform with customers? Partly, though, it’s happening subconsciously. Even if we never consciously say to ourselves that “Better grooming = better employee", we tend to act that way in our hiring.

These effects go even beyond the hiring phase — attractive individuals in the US and Canada have been estimated to earn an average of 12-14 percent more than their unattractive coworkers. Whether this is due to liking bias or perhaps the increased self confidence that comes from above-average looks is hard to say.

Appearance is not the only quality that may skew our perceptions in favor of someone. The next one on the list is similarity.

Similarity

We like people who resemble us. Whether it’s appearance, opinions, lifestyle or background, we tend to favor people who on some dimension are most similar to ourselves.

A great example of similarity bias is the case of dress. Have you ever been at an event where you felt out of place because you were either overdressed or underdressed? The uneasy feelings are not caused only by your imagination. Numerous studies suggest that we are more likely to do favors, such as giving a dime or signing a petition, to someone who looks like us.

Similarity bias can extend to even such ambiguous traits as interests and background. Many salesmen are trained to look for similarities to produce a favorable and trustwothy image in the eyes of their potential customers. In Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Robert Cialdini explains:

If there is camping gear in the trunk, the salespeople might mention, later on, how they love to get away from the city whenever they can; if there are golf balls on the back seat, they might remark that they hope the rain will hold off until they can play the eighteen holes they scheduled for later in the day; if they notice that the car was purchased out of state, they might ask where a customer is from and report—with surprise—that they (or their spouse) were born there, too.

These are just a few of many examples which can be surprisingly effective in producing a sweet feeling of familiarity. Multiple studies illustrate the same pattern. We decide to fill out surveys from people with similar names, buy insurance from agents of similar age and smoking habits, and even decide that those who share our political views deserve their medical treatment sooner than the rest.

There is just one takeaway: even if the similarities are terribly superficial, we still may end up liking the other person more than we should.

Praise and Compliments

“And what will a man naturally come to like and love,

apart from his parent, spouse and child?

Well, he will like and love being liked and loved."

— Charlie Munger

We are all phenomenal suckers for flattery. These are not my words, but words of Robert Cialdini and they ring a bell. Perhaps, more than anything else in this world we love to be loved and, consequently, we love those that love us.

“We love to be loved and, consequently, we love those that love us." Click To Tweet

Consider the technique of Joe Girard, who has been continuously called the world’s “greatest car salesman" and has made it to the Guinness World Record book.

Each month Joe prints and sends over 13,000 holiday cards to his former customers.While the theme of the card varies depending on the season and celebration, the printed message always remains the same. On each of those cards Girard prints three simple words "I like you" and his name. He explains:

“There’s nothing else on the card, nothin’ but my name. I’m just telling ’em that I like ’em." “I like you." It came in the mail every year, 12 times a year, like clockwork.

Joe understood a simple fact about humans – we love to be loved.

As numerous experiments show, regardless of whether the praise is deserved or not, we cannot help but develop warm feelings to those that provide it. Our reaction can be so automatic, that we develop liking even when the attempt to win our favor is an obvious one, as in the case of Joe.

Familiarity

In addition to liking those that like us and look like us, we also tend to like those who we know. That’s why repeated exposure can be a powerful tool in establishing liking.

There is a fun experiment you can do to understand the power of familiarity.

Take a picture of yourself and create a mirror image in one of the editing tools. Now with the two pictures at hand decide which one – the real or the mirror image you like better. Show the two pictures to a friend and ask her to choose the better one as well.

If you and your friend are like the group on whom this trick was tried, you should notice something odd. Your friend will prefer the true print, whereas you will think you look better on the mirror image. This is because you both prefer the faces you are used to. Your friend always sees you from her perspective, whereas you have learnt recognize and love your mirror image.

The effect of course extends beyond faces into places, names and even ideas.

For example, in elections we might prefer candidates whose names sound more familiar. The Ohio Attorney-General post was claimed by a man who, shortly before his candidacy, changed his last name to Brown – a family name of Ohio political tradition. Apart from his surname, there was little to nothing that separated him from other equally if not more capable candidates.

How could such a thing happen? The answer lies partly in the unconscious way that familiarity affects our liking. Often we don’t realize that our attitude toward something has been influenced by the number of times we have been exposed to it in the past.

Loving by Association and Referral

Charisma or attraction are not prerequisites for liking — a mere association with someone you like or trust can be enough.

The bias from association shows itself in many other domains and is especially strong when we associate with the person we like the most — ourself. For example, the relationship between a sports fan and his local team can be highly personal even though the association is often based only on shared location. For the fan, however, the team is an important part of his self-identity. If the team or athlete wins, he wins as well, which is why sports can be so emotional. The most dedicated fans are ready to get into fights, burn cars or even kill to defend the honor of their team.

Such associated sense of pride and achievement is as true for celebrities as it is for sports. When Kevin Costner delivered his acceptance speech after winning the best picture award for Dances With Wolves, he said:

“While it may not be as important as the rest of the world situation, it will always be important to us. My family will never forget what happened here; my Native American brothers and sisters, especially the Lakota Sioux, will never forget, and the people I went to high school with will never forget."

The interesting part of his words is the notion that his high school peers will remember, which is probably true. His former classmates are likely to tell people that they went to school with Costner, even though they themselves had no connection with the success of the movie.

Costner’s words illustrate that even a trivial association with success may reap benefits and breed confidence.

Who else do we like besides ourselves, celebrities and our sports teams?

People we’ve met through those who are close to us – our neighbors, friends and family. It is common sense that a referral from someone we trust is enough to trigger mild liking and favorable initial opinions.

There are a number of companies that use friend referral as a sales tactic. Network providers, insurers and other subscription services offer a number of benefits for those of us who give away our friends’ contact details.

The success of this method rests on the implicit idea that turning down the sales rep who says “your friend Jenny/Allan suggested I call you" feels nearly as bad as turning down Jenny or Allan themselves. This tactic, when well executed, leads to a never-ending chain of new customers.

Can We Avoid Liking?

Perhaps the right question to ask here is not “how can we avoid the bias from liking", but when should we?

Someone who is conditioned to like the right people and pick their idols carefully can greatly benefit from these biases. Charlie Munger recalls that both he and Warren Buffett benefitted from liking admirable persons:

One common, beneficial example for us both was Warren’s uncle, Fred Buffett, who cheerfully did the endless grocery-store work that Warren and I ended up admiring from a safe distance. Even now, after I have known so many other people, I doubt if it is possible to be a nicer man than Fred Buffett was, and he changed me for the better.

The keywords here are “from a safe distance".

If dealing with salesmen and others who clearly benefit from your liking, it might be a good idea to check whether you have been influenced. In these unclear cases Cialdini advises us to focus on our feelings rather than the other person’s actions that may produce liking. Ask yourself how much of what you feel is due to liking versus the actual facts of the situation.

The time to call out the defense is when we feel ourselves liking the practitioner more than we should under the circumstances, when we feel manipulated.

Once we have recognized that we like the requester more than we would expect under the given circumstances, we should take a step back and question ourselves. Are you doing the deal because you like someone or is it because it is indeed the best option out there?

Mental Model: Bias from Liking/Loving Click To Tweet

***

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

Farnam Street helps you make better decisions, innovate, and avoid stupidity.

Farnam Street helps you make better decisions, innovate, and avoid stupidity.

With over 350,000 monthly readers and more than 88,000 subscribers to our popular weekly digest, we've become an online intellectual hub.

Creating a Latticework of Mental Models: An Introduction

Mental Models — How to Solve Problems

Acquiring knowledge may seem like a daunting task. There is so much to know and time is precious. Luckily, we don’t have to master everything.

To get the biggest bang for our buck we can study the big ideas from the big disciplines: physics, biology, psychology, philosophy, literature, sociology, history, and a few others. We call these big ideas mental models.

Our aim is not to remember facts and try to repeat them when asked, the way you studied for your high school history exams. We’re going to try and hang these ideas on a latticework of mental models, with vivid examples in our head to help us remember and apply them.

The latticework of mental models puts them in a useable form to analyze a wide variety of situations and enables us to make better decisions. And when big ideas from multiple disciplines all point towards the same conclusion, we can begin to conclude that we’ve hit on an important truth.

The idea for building such a latticework comes from Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and one of the finest cross-disciplinary thinkers in the world.

Here, Charlie Munger explains his approach to worldly wisdom:

Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form.

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.

What are the models? Well, the first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does…

It’s like the old saying, “To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." And of course, that’s the way the chiropractor goes about practicing medicine. But that’s a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world. So you’ve got to have multiple models.

And the models have to come from multiple disciplines because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department. That’s why poetry professors, by and large, are so unwise in a worldly sense. They don’t have enough models in their heads. So you’ve got to have models across a fair array of disciplines.

You may say, “My God, this is already getting way too tough." But, fortunately, it isn’t that tough because 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.(1)

John T. Reed, author of Succeeding offers an important additional insight:

When you first start to study a field, it seems like you have to memorize a zillion things. You don’t. What you need is to identify the core principles – generally three to twelve of them – that govern the field. The million things you thought you had to memorize are simply various combinations of the core principles.

Mental Models

The central principle of the mental model approach is that you must have many of them. Ideally, all the ones you need to solve the problem at hand. As with physical tools, lacking a mental tool at the crucial moment can lead to a bad result.

This seems self-evident, but it’s an unnatural way to think. Without the right training, your brain takes the other approach, which is to say: Which models do I already know and love, and how can I apply them here? Munger’s analogy for this is the man with a hammer, to whom everything looks a bit like a nail. Such narrow-minded thinking feels entirely natural to us, but it leads to far too many misjudgments.

As an example, Tim Wu writes about Chris Anderson, who wrote The Long Tail, a popular 21st century business book. Here is what happens when you rely on one (powerful) mental model to solve everything.

Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail does something that only the best books do—uncovers a phenomenon that’s undeniably going on and makes clear sense of it. Anderson, the Wired editor-in-chief who first wrote about the Long Tail concept in 2004, had two moments of genius: He visualized the demand for certain products as a “power curve," and he came up with a catchy phrase to go with his observation. Like most good ideas, the Long Tail attaches to your mind and gets stuck there. Everything you take in—cult blogs, alternative music, festival films—starts looking like the Long Tail in action. But that’s also the problem. The Long Tail theory is so catchy it can overgrow its useful boundaries. Unfortunately, Anderson’s book exacerbates this problem. When you put it down, there’s one question you won’t be able to answer: When, exactly, doesn’t the Long Tail matter?

This insight goes only so far, but like many business books, The Long Tail commits the sin of overreaching. The tagline on the book’s cover reads, “Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More," which is certainly wrong or at least exaggerated. Inside we learn about “the Long Tail of Everything." Anderson’s book, unlike his original Wired article, threatens to turn a great theory of inventory economics into a bad theory of life and the universe. He writes that “there are now Long Tail markets practically everywhere you look," calling offshoring the “Long Tail of labor," and online universities “the Long Tail of education." He quotes approvingly an analysis that claims, improbably, that there’s a “Long Tail of national security" in which al-Qaida is a “supercharged niche supplier." At times, the Long Tail becomes the proverbial theory hammer looking for nails to pound.

What the book doesn’t get at is the relationship between these standards-driven industries where the Long Tail doesn’t matter, and the content industries where it does. There aren’t Long Tails everywhere.

The truth is that the good ideas are just as dangerous as the bad ones. Warren Buffett’s mentor, Ben Graham, used to put it as such:

You can get in way more trouble with a good idea than a bad idea, because you forget that the good idea has limits.

The best antidote to this sort of overreaching is to add more colors to your mental palette; to expand your repertoire of ideas, make them vivid and available, and watch your mind grow.

You’ll know you’re on to something when the ideas start to compete with one another. At first, this is mildly uncomfortable. One idea says X and the other idea says the reverse of X: How do I decide which is right?

This process of letting the models compete and fight for superiority and greater fundamentalness is called thinking! It’s a little like learning to walk or ride a bike; at first you can’t believe all that you’re supposed to do at once, but eventually you wonder how you ever got along without it. As Charlie likes to say, going back to any other method would feel like cutting off your hands.

Good luck, and let’s explore the models.

The Farnam Street Latticework of Mental Models

Human Psychology

Biases emanating from the Availability Heuristic:

– Ease of Recall

– Retrievability

Biases emanating from the Representativeness Heuristic

– Bias from insensitivity to base rates

– Bias from insensitivity to sample size

– Misconceptions of chance

– Regression to the mean

– Bias from conjunction fallacy

Biases emanating from the Confirmation Heuristic

– Confirmation bias

– Bias from anchoring

– Conjunctive and disjunctive-events bias

– Bias from over-confidence

– Hindsight Bias

Others

– Bias from incentives and reinforcement

– Bias from self-interest

– Bias from association

– Bias from liking/loving

– Bias from disliking/hating

– Commitment and Consistency Bias

– Bias from excessive fairness

– Bias from envy and jealousy

– Reciprocation bias

– Over-influence from authority

– Deprival Super-Reaction Bias

– Bias from contrast

– Bias from stress-influence

– Bias from emotional arousal

– Bias from physical or psychological pain

– Fundamental Attribution Error

– Bias from the status quo

– Do something tendency

– Do nothing tendency

– Over-influence from precision/models

– Uncertainty avoidance

– Not invented here bias

– Short-term bias

– Tendency to avoid extremes

– Man with a Hammer Tendency

– Bias from social proof

– Over-influence from framing effects

– Lollapalooza

Business

– Price Sensitivity

– Scale

– Distribution

– Cost

– Brand

– Improving Returns

– Porters 5 Forces

– Decision Trees

– Diminishing Returns

– Double Entry Accounting

Investing

– Mr. Market

– Circle of competence

Ecology

– Complex adaptive systems

– Systems Thinking

Economics

– Utility

– Diminishing Utility

– Supply and Demand

– Scarcity

– Elasticity

– Economies of Scale

– Opportunity Cost

– Marginal Cost

– Comparative Advantage

– Trade-offs

– Price Discrimination

– Positive and Negative Externalities

– Sunk Costs

– Moral Hazard

– Game Theory

– Prisoners’ Dilemma

– Tragedy of the Commons

– Bottlenecks

– Time value of Money

Engineering

– Feedback loops

– Redundancy

– Margin of Safety

– Tight coupling

– Breakpoints

Mathematics

– Bayes Theorem

– Power Law

– Law of large numbers

– Compounding

– Probability Theory

– Permutations

– Combinations

– Variability

– Standard Deviation and normal distribution

– Regression to the mean

– Inversion

– Multiplicative Systems

Statistics

– Outliers and self fulfilling prophecy

– Correlation versus Causation

– Mean, Median, Mode

– Distribution

Chemistry

– Thermodynamics

– Kinetics

– Autocatalysis

Physics

– Newton’s Laws

– Momentum

– Quantum Mechanics

– Critical Mass

– Equilibrium

Biology

– Natural Selection

More Models:

– Asymmetric Information

– Occam’s Razor

– Deduction and Induction

– Basic Decision Making Process

– Scientific Method

– Process versus Outcome

– And then what?

– The Agency Problem

– 7 Deadly Sins

– Network Effect

– Gresham’s Law

– The Red Queen Effect

***

Remember, the above list is always subject to growing and changing. We’re always trying to find better ways to organize our knowledge.

Sources:

1. Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie’s Almanack

2. John T. Reed, Succeeding

3. Alice Schroeder, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

You should follow Farnam Street on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also subscribe to the RSS feed and weekly email digest for exclusive content.

Sponsored By:

Most Popular

What Books Would You Recommend Someone Read to Improve their General Knowledge of the World?

What Are You Doing About It? Reaching Deep Fluency with Mental Models

The Chessboard Fallacy

The Best Way to Learn Anything: The Feynman Technique

Creating a Latticework of Mental Models: An Introduction

Make Better Decisions.

Join over 85,000 readers and subscribe to my free Sunday digest — a rich diet of multidisciplinary thinking.

Member Account

Sign in

Work Smarter, Not Harder.

Learn to exploit unrecognized simplicities.

(C) 2016 Farnam Street Media Inc.

This website participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program.

Farnam Street is hosted by Media Temple.

View Full Site

"The one thing I can count on to make me a little smarter every week." — Matthew M., GitHub

▲

2.1k

Shares

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

Charlie Munger: The Psychology of Human Misjudgment

farnamstreetblog.com

Charlie Munger: The Psychology of Human Misjudgment

Below is an audio copy of Charlie Munger‘s famous 1995 talk The Psychology of Human Misjudgment (transcript).

Munger, for those of you who haven’t heard of him, is the irreverent partner of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway. He’s offered us such gems as: a two step process for making effective decisions and the work required to have an opinion.

And this talk on The Psychology of Human Misjudgment is one of his best you’ll ever hear.

My nature makes me incline toward diagnosing and talking about errors in conventional wisdom. And despite years of being smoothed out by the hard knocks that were inevitable for one with my attitude, I don’t believe life ever knocked all the brashness out of the man.

… I have fallen in love with my way of laying out psychology because it has been so useful to me. And so, before I die, I want to imitate to some extent the bequest practices of three characters: the protagonist in John Bunyan’s Pilgram’s Progress, Benjamin Franklin, and my first employer, Ernest Buffett.

Charlie made extensive revisions to The Psychology of Human Misjudgment in Poor Charlie’s Almanack because he “thought he could do better at eighty-one than he did more than ten years earlier when he (1) knew less and was more harried by a crowded life and (2) was speaking from rough notes instead of revising transcripts."

Posted on October 2nd, 2016

farnamstreetblog.com Bias from Association: Why We Shoot the Messenger

Bias from Association

We automatically connect a stimulus (thing/person) with pain (fear) or pleasure (hope). As pleasure seeking animals we seek out positive associations and attempt to remove negative ones. This happens easily when we experience the positive or negative consequences of a stimulus. The more vivid the event the easier it is to remember. Brands (including people) attempt to influence our behavior by associating with positive things.

***

Bias from Association

Our life and memory revolve around associations. The smell of a good lunch makes our stomach growl, the songs we hear remind us about the special times that we have had and horror movies leave us with goosebumps.

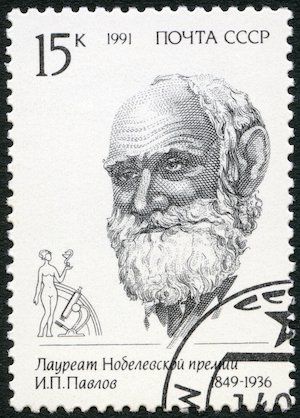

These natural, uncontrolled responses upon a specific signal are examples of classical conditioning. Classical conditioning, or in simple terms — learning by association, was discovered by a Russian scientist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. Pavlov was a physiologist whose work on digestion in dogs won him a Nobel Prize in 1904.

In the course of his work in physiology, Pavlov made an accidental observation that dogs started salivating even before their food was presented to them.

With repeated testing, he noticed that the dogs began to salivate in anticipation of a specific signal, such as the footsteps of their feeder or, if conditioned that way, even after the sound of a tone.

Pavlov’s genius lay in his ability to understand the implications of his discovery. He knew that dogs have a natural reflex of salivating to food but not to footsteps or tones. He was on to something. Pavlov realized that, if coupling the two signals together induced the same reactive response in dogs, then other physical reactions may be inducible via similar associations.

In effect, with Pavlovian association, we respond to a stimulus because we anticipate what comes next: the reality that would make our response correct.

Now things get interesting.

Rules of Conditioning

Suppose we want to condition a dog to salivate to a tone. If we sound the tone without having taught the dog to specifically respond, the ears of the dog might move, but the dog will not salivate. The tone is just a neutral stimulus, at this point. On the other hand, food for the dog is an unconditioned stimulus, because it always makes the dog salivate.

If we now pair the arrival of food and the sound of the tone, we elicit a learning trial for the dog. After several such trials the association develops and is strong enough to make the dog salivate even though there is no food. The tone, at this point, has become a conditioned stimulus. This is learned hope. Learned fear is more easily acquired.

The speed and degree to which the dog learns to display the response will depend on several factors.

The best results come when the conditioned stimulus is paired with the unconditioned one several times. This develops a strong association. It takes time for our brains to detect specific patterns.

Classical conditioning involves automatic or reflexive responses and not voluntary behavior.*

There are also cases to which this principle does not apply. When we undergo high impact events, such as a car crash, robbery or firing from a job, a single event will be enough to create a strong association.

Why We Shoot The Messenger

One of our goals should be to understand how the world works. A necessary condition to this is understanding our problems. However, sometimes people are afraid to tell us problems.

This is also known at The Pavlovian Messenger Syndrome.

The original messenger wasn’t shot, he was beheaded. In Plutarch’s Lives we find:

The first messenger, that gave notice of Lucullus’ coming was so far from pleasing Tigranes that, he had his head cut off for his pains; and no man dared to bring further information. Without any intelligence at all, Tigranes sat while war was already blazing around him, giving ear only to those who flattered him.

The number of times that happens in an organization is countless. A related sentiment exists in Antigone by Sophocles as “No one loves the messenger who brings bad news."

In a lesson on elementary worldly wisdom, Charlie Munger said:

If people tell you what you really don’t want to hear — what’s unpleasant —there’s an almost automatic reaction of antipathy. You have to train yourself out of it. It isn’t foredestined that you have to be this way. But you will tend to be this way if you don’t think about it.

In Antony and Cleopatra, when told Antony has married another, Cleopatra threatens to treat the messenger poorly, eliciting the response “Gracious madam, I that do bring the news made not the match."

And the advice “Don’t shoot the messenger" appears in Henry IV, Part 2.

If you yourself happen to be the messenger, it might be best to deliver the news first via and appear in person later to minimize the negative feelings towards you.

If, on the other hand, you’re the receiver of bad news, it’s best to follow the advice of Warren Buffett, who comments on being informed of bad news:

We only give a couple of instructions to people when they go to work for us: One is to think like an owner. And the second is to tell us bad news immediately — because good news takes care of itself. We can take bad news, but we don’t like it late.

Pavlov showed that sequence matters: the association is most clear to us when the conditioned stimulus appears first and remains after the unconditioned stimulus is introduced.

Unsurprisingly, our learning responses become weaker if the two stimuli are introduced at the same time and are even slower if they are presented in the reverse (unconditioned then conditioned stimulus) order.

Attraction and Repulsion

There’s no doubt that classical conditioning influences what attracts us and even arouses us. Most of us will recognize that images and videos of kittens will make our hearts softer and perfume or a look from our partner can make our hearts beat faster.

Charlie Munger explains the case of building Coca-Cola, whose marketing and product strategy is built on strong foundations of conditioning.

Munger walks us through the creation of the brand by using conditioned reflexes:

The neural system of Pavlov’s dog causes it to salivate at the bell it can’t eat. And the brain of man yearns for the type of beverage held by the pretty woman he can’t have. And so, Glotz, we must use every sort of decent, honorable Pavlovian conditioning we can think of. For as long as we are in business, our beverage and its promotion must be associated in consumer minds with all other things consumers like or admire.

By repeatedly pairing a product or brand with a favorable impression, we can turn it into a conditioned stimulus that makes us buy.

This goes even beyond advertising — conditioned reflexes are also encompassed in Coca Cola’s name. Munger continues:

Considering Pavlovian effects, we will have wisely chosen the exotic and expensive-sounding name “Coca-Cola," instead of a pedestrian name like “Glotz’s Sugared, Caffeinated Water."

And even texture and taste:

And we will carbonate our water, making our product seem like champagne, or some other expensive beverage, while also making its flavor better and imitation harder to arrange for competing products.

Combining these and other clever, non-Pavlovian techniques leads to what Charlie Munger calls the lollapalooza effect causing so many consumers to buy and making Coca-Cola a great business for over a century.

While Coca-Cola has some of its advantages rooted in positive Pavlovian association, there are cases when associations do no good. In childhood many of us were afraid of doctors or dentists, because we quickly learnt to associate these visits with pain. While we may have lost our fear of dentists, by now many of us experience similarly unpleasant feelings when opening a letter from the police or anticipating a negative performance review.

Constructive criticism can be one of life’s great gifts and an engine for improvement, however, before we can benefit from it, we must be prepared that some of it will hurt. If we are not at least implicitly aware of the conditioning phenomena and have people telling us what we don’t want to hear, we may develop a certain disliking to those delivering the news.

The amount of people in leadership positions unable to detach the information from the messenger can be truly surprising. In The Psychology of Human Misjudgement, Munger tells about the ex-CEO of CBS, William Paley, who had a blind spot for ideas that did not align with his views.

Television was dominated by one network-CBS-in its early days. And Paley was a god. But he didn’t like to hear what he didn’t like to hear, and people soon learned that. So they told Paley only what he liked to hear. Therefore, he was soon living in a little cocoon of unreality and everything else was corrupt although it was a great business.

In the case of Paley, his inability to take criticism and recognize incentives was soon noticed by those around him and it resulted in sub-optimal outcomes.

… If you take all the acquisitions that CBS made under Paley after the acquisition of the network itself, with all his dumb advisors-his investment bankers, management consultants, and so forth, who were getting paid very handsomely-it was absolutely terrible.

Paley is by no means the only example of such dysfunction in the high ranks of business. In fact, the higher up you are in an organization the more people fear telling you the truth. Providing sycophants with positive reinforcement will only encourage this behaviour and ensure you’re insulated from reality.

To make matters worse, as we move up in seniority, we also tend to become more confident about our own judgements being correct. This is a dangerous tendency, but we need not be bound by it.

We can train ourselves out of it with reflection and effort.

Escaping Associations

No doubt that learning via associations is crucial for our survival — it alerts us about the arrival of an important event and gives us time to prepare for the appropriate response.

Sometimes, however, learnt associations do not serve us and our relationships well. We find that we have become subject to negative responses in others or recognize unreasonable responses in ourselves.

Awareness and understanding may serve as good first steps. Yet, even when taken together they may not be sufficient to unlearn some of the more stubborn associations. In such cases we may want to try several known techniques to desensitize them or reverse their negative effects.

One way to proceed is via habituation.

When we habituate someone, we blunt down their conditioned response by exposing them to the specific stimulus pairing continuously. After a while, they simply stop responding. This loss of interest is a natural learning response that allows us to conserve energy for stimuli that are unfamiliar and therefore draw the attention of the mind.

Continuous exposure can yield results as powerful as becoming fully indifferent to stimuli as strong as violence and death.

In Man’s Search For Meaning, Viktor Frankl, a holocaust survivor, tells about experiencing absolute desensitization to the most horrific events imaginable:

Disgust, horror and pity are emotions that our spectator [Frankl] could not really feel any more. The sufferers, the dying and the dead, became such commonplace sights to him after a few weeks of camp life that they could not move him any more.

Of course, habituation can also serve good motives, such as getting ourselves over fear, overcoming trauma or harmonizing relationships by making each side less sensitive to the other side’s vices. However, as powerful as habituation is we must recognize its limitations.

If we want someone to respond differently rather than become indifferent, flooding them with stimuli will not help us achieve our aims.

Consider the case for teaching children – the last thing we would want is to make them indifferent to what we say. Therefore instead of habituation, we should employ another strategy.

A frequently used technique in coaching, exposure therapy, involves cutting back our criticism for a while and reintroducing it by gradually lowering the person’s threshold for becoming defensive.

The key difference between exposure therapy and habituation lies in being subtle rather than blunt.

If we try to avoid forming negative associations and achieve behavioral change at the same time, we will always want the positive vs. negative feedback ratio to be in favor of the positive. This is why we so often provide feedback in a “sandwich," where a positive remark is followed by what must be improved and then finished with another positive remark.

Aversion therapy is the exact opposite of exposure therapy.

Aversion therapy aims to exchange the positive association with a negative one within a few high impact events. For example, some parents teach out a sweet tooth by forcing their children to consume an insurmountable amount of sweets in one sitting under their supervision.

While ethically questionable this idea is not completely unfounded.

If the experience is traumatic enough, the positive associations of, for example, a sugar high, will be replaced by the negative association of nausea and sickness.

This controversial technique was used in experiments with alcoholics. While effective in theory, it was known to yield only mixed results in practice, with patients often resorting back to past conditions over time.

This is also why there are gross and terrifying pictures on cigarette packages in many countries.

Overall, creating habits that last or permanently breaking them can be a tough mission to embark upon.

In the case of feedback, we may try to associate our presence with positive stimuli, which is why building great first impressions and appearing friendly matters.

Keep in Mind